“I always carry dog treats in my pockets,” explains Mary Glen McClendon, showing off a home-baked biscuit that she’s labeled “Top Sirloin.”

The 12-year-old is cuddling Tilly, a graying spaniel, and Penny, a Chihuahua mix dressed in a pink polka-dot dog sweater, while simultaneously weaving sparkly purple strings into a bracelet.

She tosses back a wave of honey hair and smiles with cerulean eyes as the conversation turns to her love of pickles, Percy Jackson books and playing ice hockey with the Northern Virginia Ice Dogs. But it was only a year ago that she looked so different that even longtime friends could not recognize her.

* * *

It all started on a Thursday in May of 2015. Ashley McClendon knew something was wrong when she left work to pick up her daughter at Abingdon Elementary School in Arlington. “I looked at her,” Ashley recalls, “and I said, ‘Your eyes are yellow!’ Like, Michael Jackson Thriller yellow.” When Mary Glen threw up at school the next day, Ashley took her to the pediatrician.

Five days later, they were sitting with a liver specialist, Stuart Kaufman, at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital. The news was bad. Blood tests showed that Mary Glen’s liver was failing. She needed to be admitted on the spot.

A subsequent biopsy revealed that the fifth-grader had developed autoimmune hepatitis, a condition in which the body’s immune system malfunctions and attacks the liver.

Autoimmune diseases tend to run in families, so that aspect of the diagnosis made sense to Ashley, 43, who has Crohn’s disease (an autoimmune disorder that affects the digestive tract) and whose father and sister also suffer from minor autoimmune conditions. But Mary Glen’s situation was much more dire. Her immune system was doing so much damage to her liver that doctors feared she might need a transplant.

There was one possible alternative. The human liver is so good at regenerating itself, Kaufman explained, that Mary Glen’s liver might recover if they could just get her immune system to call off the attack. With this possibility in mind, her medical team—which had quickly expanded to include Georgetown pediatric transplant specialists Nada Yazigi and Khalid Khan—prescribed high doses of steroids to suppress her immune system.

The drugs had the immediate side effect of making Mary Glen ravenous. She began polishing off two breakfasts every morning, and then some. “We’d take her a pizza from Pie-tanza,” says her father, Trey, 46, a software designer with the Fairfax offices of CGI, a business consulting firm. “She’d eat it and then have ice cream, and then she’d want to eat again an hour later.”

After six days of treatment, blood tests showed that Mary Glen’s liver was beginning to rally. She was released from the hospital just as Trey received the terrible news that his father had died. The McClendons spent one night at home and then drove to Alabama for the funeral.

They were on their way back to Arlington a few days later when Ashley’s cellphone rang somewhere in North Carolina. It was the hospital calling. Mary Glen’s

Mary Glen goofing around with family friend Lindsey Rodriguez

doctors had been reviewing her case and had detected some other abnormalities in her blood work. She needed more tests, including a bone marrow biopsy. The next day, still tired from a 14-hour drive and emotionally drained from the funeral, Mary Glen was readmitted to Georgetown.

This time, she was in for a much longer stay of 20 days. The biopsy revealed that only 10 percent of her bone marrow was still doing its job of producing new blood cells—cells that are essential for everything from fighting off infections to clotting.

Suddenly her diagnosis was twofold. In addition to autoimmune hepatitis, Mary Glen also had aplastic anemia, a life-threatening condition so rare that it affects only 600 to 900 Americans per year. Aplastic anemia can be caused by chemotherapy and exposure to toxic chemicals, but for many patients its cause is unknown, according to the Aplastic Anemia and MDS International Foundation. In Mary Glen’s case, doctors suspected that a viral infection might have set off an autoimmune reaction.

For Ashley and Trey, the revelation of this rare condition only made their daughter’s illness more terrifying. “I don’t think [the doctors] knew enough about it to know what to expect,” says Trey. “Which means you don’t know what to expect,” says Ashley, finishing his thought. “Because they can’t really tell you.”

Remarkably, the family did have someone to lean on. In an uncanny coincidence, Ashley had a close college friend from Auburn University who suffered from the same condition. Emily McClure had been living with aplastic anemia for more than seven years in Louisiana. She had received two bone marrow transplants.

But Mary Glen’s medical team at Georgetown wasn’t ready to resort to a bone marrow transplant—at least not yet. First, they wanted to try a less invasive approach in which they would further suppress the girl’s immune system to prevent an attack on her liver while giving her infusions of platelets and red blood cells. They surgically inserted a central PICC line (a flexible tube) into a vein in Mary Glen’s arm and began administering a powerful immunosuppressant, Atgam, for six hours at a time.

Atgam is a steroid derived from the blood serum of horses and often carries the label “horse lgG” on the IV bag. Mary Glen interpreted the name as “horse leg” and couldn’t stop giggling.

Ashley remembers that odd piece of pharmaceutical trivia—and her empathetic friend in Louisiana—providing some much-needed levity on the toughest days:

“There were times when I didn’t know what to do, and I would be on the verge of tears … and then Emily would send me a funny text that said, If Mary Glen bites a nurse, tell them it’s not her fault, it’s the horse that’s trying to bite them. And it would make me laugh.”

* * *

With the aggressive drug regimen, however, Mary Glen’s problems started to snowball. The high doses of steroids sent her blood pressure soaring and caused her to become diabetic. Soon she was taking more than a dozen different medications.

“That’s when the bruising started, from all the shots,” Trey says. “It looked like she had been standing out in the driving range, about ten feet off the tee box. Just bam bam bam.”

Mary Glen was stoic and liked to crack jokes with the hospital staff, but she screamed in pain each time the nurse came to take her blood pressure or change the dressing on her PICC line.

Determined to create some semblance of normal life for their daughter, Ashley and Trey took turns sleeping next to Mary Glen’s hospital bed. The small room filled up with spare clothes, a cooler stocked with carrots and string cheese, and colorful get-well cards from Mary Glen’s classmates.

“Early on, we would sit outside and play cards, just to get out of the room,” says Trey, who teleworked from the hospital, fitting in work whenever he could at odd hours. “We were playing gin, penny a point. I think Mary Glen still owes me $12.”

Above: a hospital craft project. Right: bruises from treatment

Ashley, who had recently started a new financial consulting job, drove to the hospital every evening. She would often spend the night, shower and then head back to the office the next morning without going home. “I tried not to cry in [Mary Glen’s] presence because I knew I had to be strong for her,” she says. Soon, a red rash covered Ashley’s face—a problem that dermatologists, unable to identify a cause, ultimately chalked up to stress.

Mary Glen, meanwhile, was constantly hungry and retaining fluids because of the steroids. Her weight climbed from 71 to 112 pounds while the drugs changed the texture of her hair and caused even more hair to grow on her face and body. At one point, Trey says, her eyebrows met over her nose and reached all the way to her temples. Her face became round and moon-shaped.

As the weeks passed, friends and neighbors stepped in to help. Some took care of the dogs. Others stopped by the hospital to keep Mary Glen company while Ashley and Trey went out to grab a bite. One night a big group came to her room with an elegant dinner, complete with roasted chicken, fine china and wine for the adults.

On the day of Mary Glen’s elementary school graduation she watched the ceremony live on an iPad, propped up on a pillow in her hospital bed. She waved briefly when a teacher showed her image to the class. It was June and she had missed five weeks of school, but she was relieved to still finish fifth grade.

Moreover, her prognosis was improving. After three weeks of aggressive drug treatments, Mary Glen’s body was finally making enough blood cells for her to go home, although her white-blood-cell count was so low that she was at risk of developing a serious infection.

In preparation for her June 23 homecoming, Trey and Ashley scrubbed their Tara-Leeway Heights bungalow from top to bottom, removing anything that could harbor germs. That included all the houseplants and the fish tank that had long held a place in Mary Glen’s room.

Her own dogs were overjoyed to see her, but Mary Glen was not allowed to pet other dogs on the street. She would need to wear a mask whenever she left the house, and summer camp was out. The McClendons canceled their annual trip to Greece to visit Ashley’s family.

* * *

At home, Mary Glen’s routine medical care now fell to her parents. “For the first week it was very scary,” Ashley says. The dining room table became a makeshift nursing station, piled high with alcohol wipes, sterile gauze and other supplies.

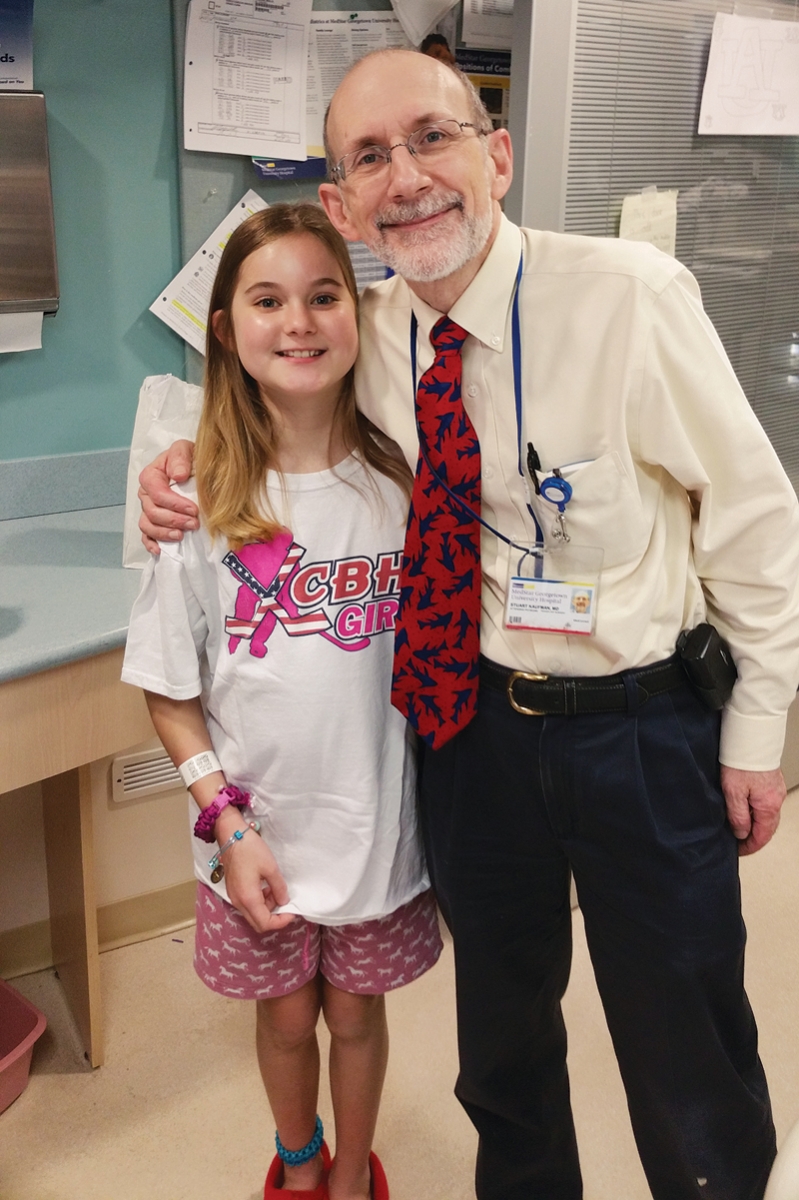

Mary Glen with Dr. Stuart Kaufman at MedStar Georgetown

Though she was making daily visits to the hospital for testing, Mary Glen needed round-the-clock care. Twice a day, Trey or Ashley donned a mask and rubber gloves, uncapped the end of her central PICC line, inserted an anticoagulant in a syringe, and then used another syringe to flush the line with saline solution to keep it from drying out. Because the tube of the PICC line snaked up the vein of Mary Glen’s arm nearly all the way to her heart, they had to painstakingly ensure each step was completed under sterile conditions.

Mary Glen was still diabetic, so they also had to test her blood sugar and inject her with insulin up to six times a day. And she was still ravenous from the steroids.

Between meals, she read mystery novels, napped and cross-stitched. To prevent her from losing consciousness overnight, Trey woke her at 2 o’clock every morning for a blood sugar test and an insulin shot. The only exception was the time she was scheduled for a bone marrow biopsy the next day and wasn’t allowed to eat after 2 a.m. On that night, he stayed up late, cooked a full breakfast of eggs, pancakes and sausages, and woke Mary Glen at 1:30 a.m. to eat it.

By the end of June, Mary Glen was well enough to go outside without a mask. Her hospital visits dropped to every other day, and soon her blood tests held good news: The treatment had worked.

Doctors began tapering her drug dosages as her immune system rebooted itself and began acting normally again. Her bone marrow began to create new blood cells—a process that she says she could actually feel: “It was just like cramps all over. Like a charley horse, but in your bones.”

Trey began coaxing her out of the house for short walks, promising a slice of pizza and a pickle if they made it to the Italian Store in Westover.

In July, the PICC line came out, and Mary Glen received permission to splash around at the Overlee Swim Club. But going out in public brought its own set of challenges. With her body and face still puffy from the steroid treatments, she was nearly unrecognizable.

“We would be at the pool and people would be like, ‘Where’s Mary Glen?’ And she’d be standing right next to me,” Ashley says, remembering how she ached to shield her daughter from those moments.

“Mary Glen said a few times, ‘Mom, I just want to look normal.’ And I would say, ‘This is the new normal. And I’m glad you’re alive.’”

* * *

Over time, Mary Glen’s diabetes cleared up and she began to eat less, but her hair was still wild when she started sixth grade at H-B Woodlawn in August. “It would actually stand up, like a lion’s mane,” Trey says.

She hid that mane under a hat every day for the first six weeks of school.

By Halloween, though, she was starting to look and feel like her old self. For her birthday on Oct. 30, she asked for donations to the Animal Welfare League of Arlington. Combining those funds with money she raised by baking and selling dog treats, she made a $450 gift to the shelter. (Trey jokes that despite his fears, mother and daughter managed the trip without adopting a third dog.)

Life generally returned to normal. But there were still a few unsolved mysteries pertaining to Mary Glen’s illness.

Mary Glen, round-faced from the steroids, with her mom, Ashley

In November of 2015, Ashley drove Mary Glen to Ohio for an appointment with Jack Bleesing, a researcher and co-director of the Diagnostic Immunology Laboratory at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital. (Nada Yazigi, the medical director of pediatric liver transplantation at Georgetown, had recommended him.) After studying Mary Glen’s case, Bleesing had several pieces of news for the family.

The first was that the aplastic anemia had come first. It’s what had caused Mary Glen’s liver to fail. “As he explained it, her bone marrow was the primary issue,” Ashley says. “The liver was just a battleground.”

More unsettling, however, was the revelation that Mary Glen’s fight with aplastic anemia might not be over. They needed to be prepared, Bleesing said, for the possibility of a lifelong illness with chronic recurrence.

“I feel like there have been times throughout this whole process,” Ashley says, “where I would start feeling so much better about how things were going. Only to be kicked in the teeth.”

Today, Mary Glen continues to go for monthly blood tests to make sure her bone marrow is pumping out new blood cells. She also receives monthly infusions of intravenous immunoglobulin antibodies. Their role, Trey explains, is to create a sort of diversion for Mary Glen’s immune system to keep it from attacking healthy tissue: “[The antibodies] kind of distract the body, like, Hey, here we are, attack us, and leave everything else alone.”

In the best-case scenario, Mary Glen will need to have her blood tested every six months at a minimum for the rest of her life. She’s also listed on the national bone marrow transplant registry “as an insurance policy,” Ashley says, in case her condition takes a turn for the worse. Though the idea of a bone marrow transplant is daunting, the registry has already found two unrelated donors who match Mary Glen on 10 out 10 blood factors—the best possible match.

* * *

Some patients emerge from illness hating the hospital, but not Mary Glen. She says the experience has only increased her interest in medicine. She’s always wanted to become a veterinarian and help animals. Now she’s even more resolved to do so.

But first there’s fun to be had. Her family hopes to return to Greece at the end of this summer to visit relatives on the island of Chios. She’s signed up for three weeks of sleepaway camp and is eager to resume her post as goalie and right wing on her hockey team this fall.

Life for the McClendons will never be the same as it was before their daughter came home with yellow eyes. There’s an innocence lost, notes the mom who now maintains a heavy three-ring binder stuffed with test results, medication lists, research studies and questions for doctors. “You have to be an advocate for your own kid,” Ashley says, “and get more than one doctor’s advice.”

At the same time, she says, there are silver linings. Like the unbridled empathy she feels for perfect strangers—and the gratitude that comes from nearly losing one of the people you love most in the world.

“I do think the experience made all of us a lot sweeter,” Ashley says. “Sweeter to each other and to others. We don’t take each other, or anything, for granted. You don’t know what tomorrow brings.”

Arlingtonian Laurie McClellan is a freelance writer and an instructor in the Johns Hopkins University science writing program. www.lauriemcclellan.com