A few months into his son’s junior year at Langley High School, Chip Kunde got worried. “His grades weren’t what they needed to be. College application time was looming, and we really felt like he needed a different environment,” says the Falls Church dad (his son’s mother lives in McLean).

After a series of family discussions, Kunde’s son agreed to transfer at the semester break to Bishop O’Connell, a private Catholic prep school in Arlington where the student body is roughly half the size of Langley’s—1,100, compared with nearly 2,000.

“We discovered he learned better in smaller classes and when he got the attention that comes with that,” Kunde says, adding that his son’s transition to a new school was surprisingly smooth for a midyear transfer. After the first day, “a group of kids took him out to Chipotle and made him feel like part of the community, even though he was new.”

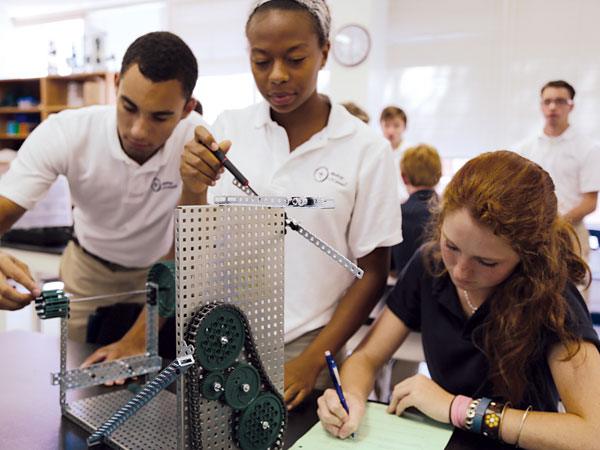

Scenes from Bishop O’Connell High School, Courtesy Photos

The teen thrived in the smaller classes, got his grades up and 15 months later was accepted to his college of choice.

Kunde doesn’t see his son’s academic turnaround as coincidental. “You’re a number at [a larger school]. It feels very impersonal,” he says, compared with a smaller campus where “everyone knows everyone.”

ONE OF THE age-old arguments for private schools (aka independent schools) is that they offer an academic lifeline in places where public education is less than stellar. That’s not exactly an issue in Northern Virginia, which is known for its high-caliber public schools.

In fact, Langley High School was ranked No. 2 on U.S. News & World Report’s 2015 list of the best public high schools in the state, second only to Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology in Alexandria. Of all the schools listed in the Top 20, 16 were in Northern Virginia.

But there are families that, nevertheless, choose to go private. Bishop O’Connell has seen an 11 percent increase in applications over the last two years, according to Head of School Joe Vorbach. It’s just one of the 38 independent schools based in Arlington, McLean and Falls Church that collectively serve nearly 6,500 students, according to Private School Review, a website that tracks and profiles private day schools nationwide.

Though parents may choose to send their kids to private school for all kinds of reasons, there is one issue that comes up repeatedly, and it isn’t prestige. It’s school and class size.

“My kids flourish in a school with no class bigger than 20 students,” says Douglas Park resident Patty Collins, whose two children, a third-grader and a sixth-grader, attend Our Savior Lutheran School, an independent pre-K–8 program in Arlington’s Alcova Heights neighborhood. “The teachers know each child’s learning level and what particular gifts they may have, and whether they need to be challenged more or need added help.”

On the matter of class size, there does seem to be a magic number. Multiple studies cited by the Center for Public Education, an initiative of the National School Boards Association, suggest that classes of 18 or fewer students correlate to an increase in student performance, particularly when smaller classes are implemented in primary grades.

And public schools—even those with outstanding reputations—are having trouble holding that line in the face of growing enrollment.

A look at Arlington Public Schools (APS) core and foreign language classes is telling. In 2010, there were 13 APS middle school classes and nine APS high school classes with 27 or more students.

By 2014, the number of classes fitting that description had jumped to 21 middle school classes and 48 high school classes.

Meanwhile, student populations in Arlington show no signs of shrinking. APS anticipates that the number of pupils countywide will grow from a current 25,649 students to 32,307 by 2024—an increase of nearly 26 percent. The county is scrambling to build new schools as existing schools overflow into a proliferation of trailers.

Similar crowding concerns are playing out in Falls Church City Public Schools, whose tiny school district will see student enrollment jump by 7 percent with a projected addition of 172 new students this fall. Fairfax County Public Schools—a much larger school district that includes schools in McLean and portions of Falls Church—will add 2,160 new students this year, realizing a 1.7 percent enrollment increase.

Patty Collins’ kids in front of Our Savior Lutheran School in Arlington, Courtesy Photo

Some parents aren’t waiting for the fallout. “I understand there’s a population explosion,” says Diana*, a local mom whose oldest child graduated from Yorktown High School in Arlington, but who moved her second child to a private high school in McLean two years ago. “It’s been extremely difficult for teachers to have a productive classroom experience when there are 26 to 28 kids in there. It’s trying to manage chaos.”

Adam*, a former public school student who is now a junior at The Potomac School in McLean, speaks from personal experience about the impact that head count can have on class dynamics. “In a class of 20 to 25, [certain kids] can be more nervous and afraid to speak up,” he says, whereas in a class of just 10 to 12 students (which he says in the norm at The Potomac School), “everyone can [make] their opinion known.”

OF COURSE private school is out of the question for many families for one simple reason: cost.

Annual tuitions can range anywhere from $6,300 at a parochial school like St. Thomas More Cathedral School in Arlington, to $37,000 at The Potomac School or Sidwell Friends School in Washington, D.C.

Families that opt to go private are essentially paying twice, insofar as they already pay taxes that support public education. This year, Arlington County will spend $19,040 per student enrolled in its schools, according to data reported to the Washington Area Boards of Educators (WABE), while Falls Church City will pay $17,109 and Fairfax County will pay $13,519 per student.

Though most private schools offer financial aid, many area families find themselves stuck in the middle—not poor enough to qualify for aid, but not wealthy enough to simply write a check.

“We’re hijacking our entire retirement to send [our kids] to elementary school,” says Karen*, an Arlington mom whose three children attend Burgundy Farm Country Day School, a private, pre-K–8 school in Alexandria.

Karen remembers being initially impressed with her neighborhood elementary school in Arlington. But halfway through her oldest child’s kindergarten year, she says several experiences changed her mind. She realized her son wanted to read but wasn’t being challenged to do so (her son reported that his teachers were too busy helping students with more pressing needs).

And though teachers raved about her son being “well-behaved,” Karen says no one was correcting his backward 7s, and “he was on the same sight words in April as he was in October.

“My child came into the school year creative, enthusiastic, energetic and loved school, and it just dripped away,” she says. “It was heartbreaking.”

A social incident is what ultimately cemented her family’s decision to leave. When her son, whom she describes as “a boy’s boy with a wide pink streak,” chose to wear pink pants to school one day, Karen and her husband talked candidly to him about what people might say. He wore the pants anyway and was teased.

This precipitated a visit to the principal’s office, where Karen says she felt “handled” and not heard.

“It feels embarrassing, to be perfectly honest, to leave the public school system and go private,” she says. “I feel so deeply supportive of public school that I’m kind of shocked I’m making this decision. [But having our son hate school] was an experiment we didn’t want to risk.”

Flint Hill School Students, Courtesy Photo

Flint Hill School Campus, Courtesy Photo

MOVING A CHILD away from his circle of friends and into a new school may be the ultimate form of parental intervention. But Becky*, an Arlington mom, says she knew she had made the right decision in sending her son to Gonzaga College High School, an all-boys Catholic high school in D.C., when he came home and said, “Everyone wants to be here, Mom.”

“That was a new experience [for him] after attending a big middle school where lots of students had negative attitudes,” she says.

Private schools often tout having cultures where it’s cool to be smart and enthusiastic about learning. And though public school classrooms certainly are not devoid of similarly driven students, they can also include disengaged kids who disrupt the vibe, says Rachel*, an Arlington parent whose children attended Sidwell Friends School and a private boarding school.

“Private schools can select their student body, and teachers don’t spend as much time dealing with some kids who just don’t want to be there,” she says.

Some would argue that’s not entirely a good thing. Public school advocates point out that students in sheltered academic settings may not encounter the broad spectrum of motivation levels and personality types that they will one day face in the real world and the workplace. Such diversity can serve as its own type of education.

“Going to [public] school with poor kids and rich kids, black kids and brown kids, smart kids and not-so-smart ones, kids with super-conservative Christian parents and other upper-middle-class Jews like me was its own education and life preparation,” Slate editor Allison Benedikt wrote in a 2013 “manifesto” in said online publication.

And yet, that sheltered, more protective environment is exactly what some private school parents say they are buying into. “When [kids] feel known and valued, it frees them to feel safe and be more ready to learn” says Waycroft-Woodlawn resident Sandra Busching, whose boys attended Rivendell School, an independent faith-based school in Arlington’s Leeway-Overlee neighborhood. (A former teacher, Busching now serves as the community relations coordinator for Rivendell.) “They feel very much at home there.”

Smaller academic settings can be particularly nurturing for kids with low self-confidence, adds Brian Lamont, director of the middle school program at the Flint Hill School in Oakton. “The concept of safety is really important…and that takes a lot of forms, not just beating up in the hallways,” he says. “What parents are looking for is that emotional safety that paves the way for academic growth. If [students are] comfortable, then they’re more likely to raise their hand in class.”

Counseling support also plays a big role, particularly when students start thinking about college. Whereas a public high school guidance counselor might work with 100 students, their private school counterparts usually have 30 to 50, observes Michelle Scott, director of the Tutoring Club of McLean, whose clients include both public and private school students.

IS THE GRASS greener on private property where test scores are concerned? National studies suggest that private school students don’t necessarily outscore their public school counterparts on standardized achievement tests. But the so-called “testing culture” that has emerged around Virginia’s Standards of Learning (SOL) requirements is precisely why some families bail on public school and go the private route. (Though most private schools use various forms of standardized tests and assessments, they generally place less emphasis on testing than public schools do.)

“Come March to June, it’s all about SOLs, and a lot of parents get frustrated with that,” says Neha Desai, director of Mathnasium of Arlington, a local math tutoring company.

The weeks leading up to SOLs—during which significant public school time is devoted to test prep and review—can be torture for kids with testing anxiety or learning differences such as ADHD. Not to mention for teachers who would rather devote those precious classroom hours to more creative endeavors.

Vivian*, a local mom, puts it bluntly: “The good teachers in public school are [screwed] by the bureaucracy. Their hands are tied and they can’t do their jobs properly.”

Though her two older children thrived in (and graduated from) Arlington public schools, Vivian says she sent her younger daughter to private school as a sophomore simply to preserve her love of learning. Her daughter was doing “fine” in public school, but she just wasn’t excited about school and wasn’t connecting with her teachers.

“The question is, What happens to the average kid?,” asks the Arlington mom, a self-described “average student” whose own parents sent her to private school for the same reason. “My mother’s comment to me then was, ‘If you make one more diorama, I’m going to slit my wrist,’ ” Vivian recalls. “Today’s diorama is the PowerPoint presentation.”

In a smaller academic setting, average students are more likely to be engaged and less likely to fall through the cracks, she contends. (There’s that size issue again.)

To the extent that private schools represent the proverbial “small pond,” they can also encourage would-be wallflowers to come forward on the extracurricular front—whether it means trying out for a part in the school play or seeking a spot on the lacrosse team. “For some families, private school is a chance for their student to participate more and maybe become more of a leader in that school environment,” says Scott of the Tutoring Club of McLean.

Matt*, a junior at Flint Hill who describes himself as “not a very confident person,” got involved in student government—something he says he wouldn’t have done at a larger school. “I’m able to contribute without feeling like I’m putting myself out there too much,” he says.

HAVING A CHILD diagnosed with learning disabilities can also prompt some parents, including those who have always advocated for public schools, to investigate private alternatives. Though public schools do differentiate and often pull students with IEPs (Individualized Education Plans) into small groups with specialists, some parents worry that their children will fail to thrive in the larger class—or that they may feel singled out or labeled.

“When a child knows they have something different about them, it affects their self-esteem,” notes Lisa Elkin, a psychologist based in McLean. “They can become depressed and frustrated if they’re getting bad grades and feel bad about themselves.” At which point academic issues begin to spill into emotional ones.

That’s when smaller classrooms where teachers have creative latitude can be beneficial, says Sarah*, a McLean mom whose two children were diagnosed with learning differences in elementary school. Her older son now attends The Lab School of Washington, a private school in the District that focuses on students with special needs in grades 1 to 12. “I’m so happy now because he seems to be learning for the sake of learning,” Sarah says.

In some cases, smaller classes can even contribute to the early detection of learning disabilities, says Tracy*, whose middle-school-age son goes to Flint Hill. She credits his small class size (about 17 kids) and an attentive teacher for the early diagnosis of his ADHD.

“If my son had been in a [public school] class with 29 kids in second grade when [his teacher] first started to notice the difference, he would have been lost completely,” says the Falls Church mom, whose son would otherwise be enrolled in Fairfax County Public Schools. “His teacher recognized very quickly that his work was not meeting his intelligence.”

Many who choose private school do so for reasons that revolve around educational philosophy—whether a family is seeking a community that aligns with its religious beliefs, a more dynamic setting for experiential learning, or a school that doesn’t overemphasize academics at the expense of play.

Washington Waldorf School, Courtesy Photo

Lincoln Kinnicutt, an Arlington parent who teaches at the K-5 Potomac Crescent Waldorf School (which will soon relocate to Fairlington), sends his child to the Washington Waldorf School in Bethesda.

“The whole Waldorf curriculum is quite balanced between artistic work, academic work, outdoor time, free time and teacher-led time,” he explains. “It’s a very diverse experience.” Other families believe that their children are best served by an education that includes religious values—something the public schools can’t do by law.

“The term Christian can have a lot of baggage for people and they might picture children walking in lockstep,” says Falls Church parent Adrienne Varner, whose kids attend Rivendell School. “It’s not like that. The curriculum is taught through a biblical lens, which is compatible with the way we teach at home.”

Donaldson Run resident Jim Rubinger admits to being at first “surprised and a little skeptical” when his eldest daughter wanted to apply to Georgetown Visitation, an all-girls Catholic school in D.C. But he’s since become a believer in same-sex education, as his three younger daughters have followed in their older sister’s footsteps.

“Particularly for girls of that age, they get to flourish and become confident in themselves, which might not happen to that degree if there were boys all day,” Rubinger says. “Without that daily adolescent social stuff going on, they really become very self-assured in that environment.”

Washington Waldorf School, Courtesy Photo

Kate*, a freshman at Visitation, agrees: “There’s a lot of drama [in a coed school] that I’m really happy I don’t have to deal with.” She also likes the fact that students wear uniforms and don’t wear tons of makeup. “It’s nice not having to spend so much time thinking about what you wear.”

PRIVATE SCHOOLS have their drawbacks. Expense notwithstanding, there can be commuting headaches in the absence of busing options. There may be differing standards for teachers (who may or may not be required to hold education degrees, though some might even have Ph.D.s, depending on the school).

And smaller isn’t always better. Public schools, by nature of their larger size, offer more extracurricular activities, more sports teams, larger facilities and enough critical mass to stage college and career fairs on location.

In spite of proactive recruiting efforts, most private schools continue to be less socioeconomically and culturally diverse than public schools. There are parents who choose public school simply to avoid having their kids grow up in an environment of “privilege.”

Some students also find the intimacy of a small prep school stifling, in that everyone knows everyone else’s business. And here’s another instance where smaller is not necessarily advantageous:

Critics note that cutthroat competition to get into elite colleges and universities can be even more pronounced in a small independent school, where handfuls of students with exemplary GPAs, glowing recommendation letters and near-perfect transcripts are competing for limited admissions spots.

In the end, choosing the right learning environment ultimately boils down to the needs of each family and the temperament of each kid.

Jordan*, who lives in Arlington, says he enjoyed many aspects of his middle school experience at an all-male private school in D.C., which came with an annual tuition of $20,000.

Academically, “it set me up very well for the intensified classes I’m taking in high school,” says the teen. But socially, he says, he felt limited being in a same-sex environment with fewer than 50 students.

Now at Yorktown High School, he’s starting his sophomore year with the most rigorous course load possible. And a social circle that includes girls.

A product of public high school, Amy Brecount White has three children who attended a mix of public and private schools.