Jennifer*, an Arlington mom of two, still shakes her head in amusement when she thinks of the award that her daughter, then a kindergartner at Nottingham Elementary, received for doing her homework all year long.

“She and a classmate were the only two kids in the class who got the award,” Jennifer says. “The other mom and I looked at each other, and we both had the same reaction: ‘Wait, we were the only ones doing this all year? We thought everyone was doing the homework!’ ”

Jennifer took the news in stride, but the revelation did broaden her perspective on the homework issue and how important—or not—it was for her daughter to complete all those weekly assignments. “In retrospect, we probably could have eased off on the homework,” she says good-naturedly. “We just didn’t know it.”

Is there an unwritten rule about how much homework effort is adequate? If so, parents like Jennifer would love to know what that is. In kindergarten, a take-home assignment might involve corralling a fidgety, tired or eager 5-year-old for 15 minutes of sorting words based on their letter sounds, or tracing a dot-to-dot picture that reinforces which numbers come after 20.

Middle schoolers in Arlington, Falls Church and McLean can have up to 90 minutes worth of work per night in four or five subject areas combined, including algebra and a foreign language.

And of course the load is even heavier for high school students, who can expect to spend three hours or more on tasks such as studying for an exam, researching a global issue, or solving a set of physics or calculus problems.

Some local parents feel it’s just too much. They want their kids to learn and succeed as much as anyone, but they also believe excessive homework is hurting family time, stressing their children out, and taking away from the physical activity, creative play and downtime that they think most kids need to be happy and healthy.

“I remember doing a first-grade project with my son,” says Susan Land, who lives in Arlington’s Williamsburg neighborhood (her son is now a fourth-grader at Nottingham). “It was cute, but at times it was like pulling teeth. He was 6—he wanted to play.”

Many teachers, meanwhile, maintain that homework, when assigned appropriately, helps students learn the material and build responsible habits, whatever their age. “When they don’t do the homework, they are always playing catch-up in class,” says Maria Clinger, a Spanish teacher at Swanson Middle School. “They are distracting themselves by not coming prepared.”

In older grades, a certain amount of extracurricular work is inevitable. “Reading a full-length novel is impossible in class,” says Rachel Sadauskas, an English teacher at Yorktown High School whose students study classics such as Beowulf and Macbeth. “You need to do that outside of class.”

But the cumulative effect can be crushing for students. “I definitely felt overwhelmed,” says Annie Mothershead, a sophomore at George Mason High School in Falls Church City, who generally had one to two hours of homework every night as a freshman. “Sometimes I didn’t finish it all.”

And yet, her rigorous schedule this year includes two foreign language classes, as well as honors English, honors chemistry and AP government—courses that college admissions officers have come to expect.

The stress associated with such workloads has led some academics to question whether homework really improves student achievement in any meaningful way. “I am not convinced that homework is useful at all,” says Robert Tai, an associate professor in the Curry School of Education at the University of Virginia and a former high school physics teacher in Illinois and Texas. “Unless teachers are really specific about what homework is supposed to do, it just chews up time.”

The recent increase in homework is not just parents’ imagination—at least not among younger grades.

According to national research by social demographers John F. Sandberg and Sandra L. Hofferth, the percentage of students between ages 6 and 8 who said they had homework on a given day has almost doubled in less than a generation, from 34 percent in 1981 to 58 percent in 1997 to 64 percent in 2002.

As the prevalence of homework has increased, so has the time demand on students. Sandberg and Hofferth found that this age group (generally kindergartners, first-, second- and third-graders) spent just 52 minutes per week on homework in 1981. That average grew to 118 minutes in 1997 and 156 minutes—more than 2.5 hours—in 2002.

This shift troubles parents like Linda Cote-Reilly, an associate professor and chair of psychology at Marymount University in Arlington. “I feel like [homework] added another hour on to his school day, and he really needed to run around and have decompression time instead of another hour of work,” she says of her older son, now a third-grader at Barrett Elementary School.

Parents also wonder how involved they should be in the process. Should they nag their children until their homework is done? Should they check their kids’ worksheets and tell them how to correct any errors? Should they stay out of it and let their kids fail or succeed on their own?

“I don’t have the guidance to know how much to help,” says Christina Klinger, a Waverly Hills resident who has a kindergartner and a second-grader at Glebe Elementary School.

“I think it really depends on the child,” says Lisa High, assistant superintendent of curriculum, innovation and personnel for Falls Church City Public Schools. “If the child is less mature and can’t take that ownership, then the parents should be involved at a level that they are comfortable with, but still allow the child to learn, and they should do this in coordination and conversation with the teacher.”

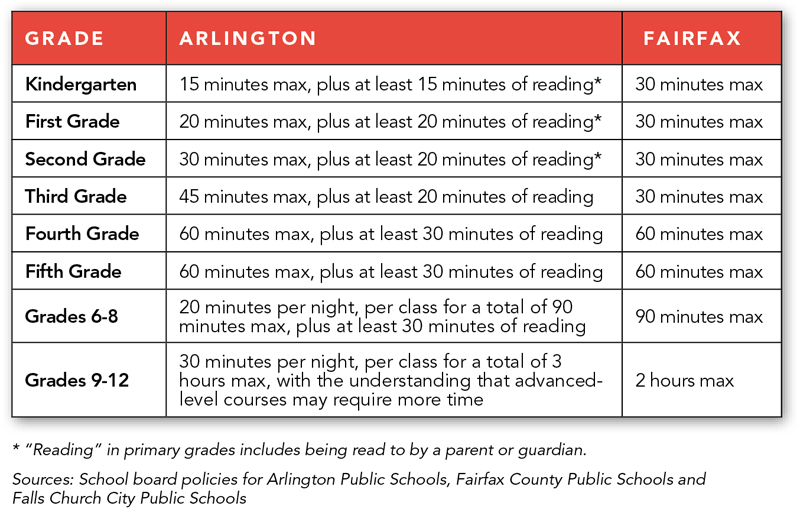

Although Falls Church City Public Schools supports the general concept of homework, it does not specify homework minimums or maximums, leaving the quantity of extracurricular work up to teachers. But the requirements are more prescriptive in Arlington and Fairfax counties, where homework “maximums” have been decreed by the school boards.

Arlington first-graders, for example, are expected to complete no more than 20 minutes of homework per night, plus an additional 20 minutes of reading. For high school students, the maximum is three hours per night—with the caveat that students in advanced academics may need to work overtime.

Some see these metrics as arbitrary, given that kids seldom fall into a one-size-fits-all time window. “As a parent, should I stop my child after he has worked at his homework for 20 minutes, if that is the allotted maximum homework time per day? Or should I insist that he finish?” asks Cote-Reilly, noting that some assignments take far longer than the estimated time frame.

“When [my son] got into first grade, he had daily homework, and that was very difficult,” she recalls. “It would take us about 45 minutes…and I say ‘us’ because I don’t feel they can do it by themselves at that age.”

Teachers say homework can be a helpful gauge of where kids are academically. “I have a good idea of who is taking longer to do the homework,” says Jaim Foster, a second-grade teacher at Barrett Elementary who is taking a leave of absence this year to serve as president of the Arlington Education Association, a teachers’ advocacy group. “I can see by the quality of the work being sent back and by the condition of the paper.”

If a student is struggling, Foster says he’s usually willing to work with the family to adjust the amount or content of the work sent home. “We want to make sure homework is valuable,” he says. “We do not want to frustrate them.”

Admittedly, many parents dislike homework’s impact on their home life (and resent the fact that it creates extra work for them).

“I am pretty sure at this age that hurrying through homework each night with frazzled parents barking at them is not productive. Then, when they are done with math and word study, we demand that they read books,” says Klinger, the Waverly Hills mom. “Personally, I would like a chance to ask them about their day in a better frame of mind and learn from them what they learned in school.”

She’s not the only one. “I’ve been struggling for several years with how to approach changing the homework policy,” says Land, a part-time systems analyst at Fannie Mae. Like other parents, she questions the value of having younger kids planted at the kitchen table when they could be playing outside—particularly in light of the widespread concerns about rising childhood obesity. “Homework is very sedentary,” she says. “People tend to think about video games as sedentary, but so is sitting at a desk.”

Land is also skeptical of the argument that homework helps young students develop study habits that will carry them through higher grades. “He’s going to drive a car one day, but that doesn’t mean I need to get him started on that now,” she says. “When we start giving homework in kindergarten, we’re killing the excitement of homework being a mark of being a ‘big kid.’”

Similar frustrations have led some parents to commit minor acts of “civil disobedience.” When Cote-Reilly’s son came home with a weekly reading log in kindergarten, she chose not to complete it. “Reading is part of our bedtime routine,” she says. “I don’t feel I need to document it for the school.”

Liz Vance, who lives in Arlington Forest, took her protest even further. “I have a seventh-grader at Jefferson and a second-grader at Barrett, and we struggled daily with homework for my older child,” she says. “It would ruin the night, every night. Instead of going outside and doing the stuff a kid should be doing, he was stuck at the table, working on the same things he had just spent the last eight hours doing. He’d do his homework, and if he was lucky enough to finish early, he might get to play a little bit before dinner and bed. But there were several nights where the only thing he had time for was homework. No wonder he hated school.”

After that experience, Vance took a different approach with her daughter. “My first-grader does no homework. I told the teacher before she even started that we would not be doing it unless she really wanted to. Instead, she comes home, has a snack and then goes outside to play. And she is excelling at school.”

Homework loads may have grown exponentially for elementary students in recent years, but at the high school level, researchers have found that the quantity has remained fairly steady for decades. That translates into about 1.7 hours of homework on a weekday and 2.4 hours on the weekend, according to a 2008 report by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Homework loads may have grown exponentially for elementary students in recent years, but at the high school level, researchers have found that the quantity has remained fairly steady for decades. That translates into about 1.7 hours of homework on a weekday and 2.4 hours on the weekend, according to a 2008 report by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The exception, of course, would be the students taking Advanced Placement (AP), International Baccalaureate (IB) and other academically demanding courses in the hopes of improving their chances of getting into a selective university or earning college credits early. In 2012, more than 2,200 Arlington Public Schools (APS) students took a total of 4,423 AP exams. And they did well. According to APS, 58.8 percent of the county’s 2012 graduates scored high enough on at least one AP exam to either get college credit or qualify for more advanced coursework in college. That’s significantly higher than their counterparts statewide (27 percent) or nationally (19.5 percent).

Arlington’s IB program is smaller—411 APS students took 1,057 IB exams in 2012—but just as competitive. In Arlington, 95 percent of 2012 graduates who sought an IB diploma received one, compared with 73 percent in Virginia and 67 percent nationally.

For these kids, and their families, extracurricular work is simply inescapable. “If your child is in AP or IB, you have to expect they will have a metric ton of homework,” says John*, an Arlington County high school math teacher who did not want to use his real name.

Fellow teachers agree that the curriculum leaves no alternative. “We can’t lower our standards,” says Maria Clinger, who taught biology at Yorktown before shifting to Swanson as a Spanish teacher. “The homework in my AP class was the heaviest because of the time constraints—you have to cover so much material. I really tried to mimic what was in a college class.”

For that reason, Clinger urges students—and parents—to be realistic about the demands of such classes. “Some kids are taking the equivalent of a college course in two or three subjects, and then they are surprised when they have homework,” she says. “Is everyone the LeBron James of academics? I would never say, ‘Don’t sign up’ for a class, because you never know the moment a kid will grasp that material. But take [one] AP class, not three. Ask yourself, ‘Am I going to enjoy reading for my biology class for an extra five hours a week or will it be torture?’ ”

One sticking point for Arlington juniors and seniors may be that there are no subtle gradations when it comes to core subjects; students can either take the regular course (which some perceive as easy and less interesting) or the AP/IB version, which may prove difficult, but will look good on their college applications.

“The intensified version of English is very, very different from the regular class,” observes Paul Petrich, a junior at Washington-Lee, whose course schedule this year includes IB chemistry, AP U.S. history, precalculus and yes, AP English. “They expect you to read the book [at home] and you spend time in class analyzing it and talking about it, whereas in the regular class, you’re reading the book in class.”

That seemingly wide gulf between regular and advanced classes concerns parents like Elissa McGovern. As a seventh-grader at H-B Woodlawn, her daughter Grace has already written a five-page research paper, with citations, on Continental Congress member Oliver Ellsworth. By contrast, McGovern says that her older daughter graduated from Washington-Lee in June with little to no experience writing formal research papers.

“You shouldn’t have to be an IB student to present a research paper,”she says with some consternation. “No matter your career, the inability to communicate can be catastrophic.”

Given their family’s experience, McGovern and her husband, Stephen Goldman, worry that regular students are not being adequately prepared for what comes next, whether it’s college or the workforce. “My daughter is going to art school to study photography, so [not knowing how to do a research paper] is not a huge issue, but for other people, it might be,” Goldman says. “I think that’s something they need to [teach in] standard courses as well.”

But there doesn’t seem to be a middle ground. When Paul Petrich’s mother, Leslie Mead, saw her son’s junior-year course schedule, she suggested he lighten his load by taking less challenging classes in the subjects that weren’t his strongest, but he wasn’t interested. “It feels like the kids graduating from the basic classes should be prepared for college, and I’m not sure that’s happening,” says Mead. “But I also think there’s a whole other story about whether we are demanding too much out of these kids [in] accelerated classes.”

Teachers, meanwhile, say they know that students sometimes feel pressured to take on more than they can handle.

“There has to be a balance between what colleges expect versus your own happiness, but it’s hard to find that balance when you have a dream college,” says Sadauskas, the English teacher at Yorktown. “I think students do get adequate counseling [about the workload they will encounter with such a schedule], but they also get the messages about how fierce the competition is to get into college.”

Of course, some students truly are extraordinary. “I wanted to do full IB because I wanted to challenge myself,”says Forest Glen resident Vincenza Montante, who graduated from Washington-Lee in June. During her senior year, she says she generally had two hours of homework on weeknights and four to seven hours over the weekend. “It wasn’t as bad as I thought it would be. But I have pretty good time management skills.”

That she does. Montante, who will attend the College of William & Mary this fall, got most of the materials for her five college applications ready the summer before her senior year.

How do education experts gauge the true value of extracurricular study? It varies. When it comes to studies of homework and its impact, “the research is not very well done,” says Tai, the University of Virginia professor. He points out that many studies look at “a single classroom or a single school” and then attempt to draw universal conclusions for or against homework based on that small sample.

Given how much schools can differ—even within the same district—in terms of student demographics, instructional approach and teacher experience, “it’s hard to take what happens at one school and apply it to another school,” he says.

And yet, researchers do seem to agree that take-home work for elementary students may be unnecessary. Numerous studies examining homework and academic achievement at those levels have found “no strong evidence for homework in the younger grades,” Tai says.

To cite one representative example, fourth-graders who did about 30 minutes of homework every night scored about the same on the 2000 fourth-grade math exam as students who did no homework, according to data from the National Center for Education Statistics.

In higher grades, the correlation between homework and academic achievement does appear stronger, according to researcher Harris Cooper, a professor of education and chair and professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University.

But quantity matters. One often-cited 1996 study by J.W. Lam at the University of Texas-Arlington suggests that a moderate amount of homework in high school has the strongest association with student achievement, as measured by standardized tests. Those students who did fewer than seven hours or more than 20 hours of homework per week did not perform as well, suggesting that excessive amounts of homework are counterproductive.

Which may explain why Fairfax County policy specifies two hours per night as the maximum amount of homework that can be assigned to its high school students. “Once you get past two hours, the research shows that the returns begin to diminish,” says Craig Herring, a former math teacher at McLean High School who is now director of pre-K–12 curriculum and instruction for Fairfax County Public Schools.

Other school districts and individual schools are starting to share this view. In California, the Los Angeles Unified School District recently decided that homework could count for no more than 10 percent of a student’s course grade at any level. Closer to home, Cunningham Park Elementary School in Vienna and South Lakes High School in Reston have adopted their own “homework bill of rights” with rules that prohibit teachers from assigning homework over holidays and also limit the weight that homework can carry in a student’s final course grade.

Still, some critics argue against homework at any age, advocating instead for an educational approach that allows for more creative teaching, less rigid assessments and more decision-making by students in their learning.

“There is no argument for making kids do…what amounts to a second shift,” says Alfie Kohn, a free-thinking former teacher, author and vocal critic of standards-based education. He has written 12 books, including The Homework Myth: Why Our Kids Get Too Much of a Bad Thing (2006).

Kohn, who lives in Boston, is frustrated that so many debates fixate on the quantity or quality of homework, rather than tackling the larger question of whether homework—as generally assigned in today’s classrooms—is justified at all. He sees the push for homework as “part of the larger phenomenon of school reform, which is a top-down, heavy-handed, test-driven approach that doesn’t differentiate between ‘harder’ and ‘better.’

“Teachers aren’t being held accountable for better learning,” he contends. “They’re being held accountable for higher scores on terrible tests.”

Teachers wrestle with the role of homework, too. Ask for an educator’s opinion on the practice, and you will frequently hear how his or her approach has evolved over the years.

“There were parts in my early career when I did assign homework because it was just the expected thing to do,” says Cherrydale resident Dana Cook, a former elementary school special-education teacher who left the classroom to stay home with her two children, now 6 and 4. But as the curriculum became increasingly academic, even for her self-contained special-education students, Cook began wondering if homework was really necessary for all those kids, all the time.

“Kids already spend so much time in school doing paper-and-pencil tasks,” she says, recalling how she began assigning homework only as needed for individual students, or suggesting more creative activities to reach a particular child’s academic goals. “We’d say, ‘Let’s forget about pencil-and-paper homework. How about taking your child to a museum?’ Because your child needs to develop language skills, which could be done by talking about the paintings in the museum.”

Of course, creating and assigning appropriate homework can be staggeringly time-consuming for teachers. At Barrett Elementary last year, Foster says he often collaborated with his colleagues to develop the weekly homework packets—all four versions. That included separate packets for “regular” students, special-education students, academically advanced students and English-language learners.

If Foster knew a student was having trouble, he might tailor a packet even further, with different proportions of math or reading as needed.

“We’re trying to be very deliberate in the skills we are asking [students] to practice,” he says. “I don’t want homework to be a waste of time.”

Like many teachers, Foster sees homework as an opportunity for students to develop not just their academics but also good habits, such as responsibility and self-discipline.

But with so many variables, others wonder if assigning—and grading—homework is really fair, given the variety of home environments, parental education and other factors that go into completing an assignment.

As a high school teacher for a dozen years, Bridget Loft routinely assigned homework to the students in her history, government and AP government classes. “I had mixed success,” says Loft, who is now the principal of Swanson Middle School. “It wasn’t until I came to middle school [in 2006] that my perspective started to evolve.

As an administrator, Loft says, her perspective has broadened. Working with multiple teachers and multiple classrooms, she sees that students encounter many challenges in tackling homework—not all of them academic.

“It was pretty telling to see how some students struggled with the organizational skills—planning, writing assignments down, organizing assignments, restating expectations and directions—necessary to be successful when tackling homework, while for others it was smooth sailing,” she says.

“In my opinion, grading students on completion of homework assignments reflects more on their abilities to organize themselves and their materials and whether or not they have access to the necessary resources,” Loft says. “[Those factors weigh more heavily] than their mastery of the content.”

Homework Hints

- Most educators consider homework a way of sharing with parents what their child is learning, so be sure to contact the school if you are uncertain why something is being assigned.

- Hate word-study homework? Dana Cook, an Arlington parent and former teacher, sometimes takes an approach that is more playful with her daughter, a rising first-grader at Key Elementary. “I’ll do the word sort and do it wrong,” she explains, thereby inspiring her daughter to “fix” her mom’s work.

- If homework takes longer to complete than advertised, try setting a timer when your child sits down to do homework so that he or she spends only the time expected for that grade level or subject. When the timer goes off, ask your child to draw a line on the paper that marks how much he or she has accomplished. “That always gave me a lot of feedback as a teacher,” says Craig Herring, director of pre-K–12 curriculum and instruction for Fairfax County Public Schools and a former math teacher at McLean High School.

- Resist the temptation to correct your child’s mistakes on a homework assignment, whatever their age. “If the homework is coming in perfect every time, then I don’t know what the student is struggling with,” Herring says. “The teacher isn’t getting the feedback that he or she needs.”

How Much?

School board policies regarding homework vary in Arlington, Fairfax and Falls Church City. While Arlington sets time expectations for nightly reading and homework, Fairfax does not differentiate between reading and homework. It also has lower maximums than Arlington, as the chart below shows.

Falls Church City skips the numbers in favor of this three-sentence policy: “Homework can provide an essential communication link between the school and the home and is an integral part of the instructional program. Homework will be assigned according to the academic program and the needs of the students in a given class. It should be an expansion and enrichment of the material taught in the classroom and should assist the student in developing deeper understanding, good work habits, and the wise use of time.”

Alison Rice wrote book reports for fun in second grade, but got busted by her teacher for failing to complete math worksheets. She probably would have loved word study homework.

*Some names have been changed for privacy.