WHEN JOE HORGAS got the call, it had been two years since his last homicide investigation. The year was 1987, and murders were rare in Arlington.Even though Horgas had been an Arlington County Police detective for nine years, the burly ex-football player, who describes himself as “a persistent kind of fella,” spent most of his time working robberies and assaults. But earlier on the evening of Dec. 1, someone had called the police about a neighbor who was missing.

A short time later, the cops found Susan Tucker, a 44-year-old writer, lying on her bed in Fairlington with her hands tied behind her back. She had been raped, then strangled with the white cord that remained looped around her neck. It was a horrifying scene.

The worst part was, Horgas and the other detectives had seen it before.

Four years earlier, in a house just a few blocks away, 32-year-old lawyer Carolyn Hamm had been raped and strangled in a similar fashion. Like Susan Tucker, Hamm lived alone. She was found with her hands bound behind her back on Jan. 25, 1984.

But an arrest had already been made in the Hamm case. Two weeks after Hamm’s body was discovered, detectives had arrested David Vasquez, a janitor at a local McDonald’s, who confessed after two eyewitnesses placed him on the street that day.

Vasquez was now serving a 35-year prison sentence downstate, although police had doubts about his role in Hamm’s murder, given that he had an IQ of less than 70. They suspected that Vasquez wasn’t capable of committing such a crime by himself and wondered if perhaps he had had a partner who was still at large.

Meanwhile, leads were slim on the Tucker case, Horgas recalls. (Now 69, he lives in Florida, where he works full-time supervising federal background investigations.) No one had seen a strange man in the area. The killer had left no fingerprints or fibers behind. He’d wiped off the surfaces he touched. He had even rubbed his footprint off the washing machine he stepped on after climbing through the basement window of Tucker’s home.

With no suspects, Horgas focused on the missing partner theory. After 3½ years in prison, surely Vasquez would be ready to give up the name of his accomplice in the Hamm murder, he thought.

On Dec. 7, the detective drove to Buckingham Correctional Center in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. From the start, the interview didn’t go well. Vasquez seemed confused. He retracted his confession. He insisted that he couldn’t have killed Hamm, because he didn’t drive and couldn’t have gotten to her house after his shift at McDonald’s ended. Although he was desperate to get out of prison, Vasquez also couldn’t name an accomplice.

“I don’t think Vasquez belongs here,” Horgas told the warden as he left. “He’s innocent.”

Pictured Above: Former Arlington County Police Detective Joe Horgas

The file included a report about a crime on Dinwiddie Street, only two blocks from Hamm’s house, which had taken place around the time of her murder. Someone had broken into a residence through a downstairs window and left some cords cut from a venetian blind on a woman’s bed, but the intruder left before the woman returned home.

Around the same time, a woman who lived nearby was assaulted by a man who broke in through a window—a man the police called the “black masked rapist.”

Between June 1983 and January 1984, in fact, nine women in Arlington had been attacked by an African-American man in his 20s who carried a knife and wore a makeshift mask. The last rape had occurred the day Carolyn Hamm’s body was found. What if the masked rapist and the murderer were the same person?

Horgas was pondering this question the next day when he came across a teletype alert from Richmond that made his hands shake. The alert detailed two recent murders on Richmond’s affluent Southside. Debbie Davis, an accounts clerk, had been found dead in her apartment on Sept. 19, 1987. Susan Hellams, a neurosurgeon, had been murdered on Oct. 3. Both women had been raped, strangled with nooses and left with their hands bound. There were no fingerprints and no witnesses.

After the second murder, it was clear that a serial killer was stalking the city of Richmond. Hardware stores sold out of window locks and yards were lit up all night along. Newspapers began calling the murderer the “Southside Strangler.”

Horgas immediately picked up the phone and got Detective Glenn Williams of the Richmond police force on the line. In a Southern drawl, Williams described a remarkably bold third murder that had occurred on Nov. 21, just over the Richmond city line: A high-school student named Diane Cho had been killed in her family’s apartment while her parents and brother slept in nearby bedrooms. The killer had entered through a second-story window, bound Cho’s hands, raped her and strangled her with a rope.

Thinking of the masked rapist in Arlington, Horgas asked Williams if anything else was happening in Richmond. That’s when Williams mentioned a recent attack in the same neighborhood where Davis and Hellams had lived. A black man wearing a mask had entered a woman’s apartment through a window and was tying her up when her neighbors heard noises and came to investigate. The man fled and had not been caught.

Struck by the similarities between the cases, Horgas told Williams about the Arlington murders, but Williams was skeptical of any connection. Arlington was too far away, he said, and according to psychological profiles prepared by FBI experts, serial killers were almost always white.

Williams then mentioned that Richmond police were trying something new to solve their cases—a method called DNA testing, which identified the unique genetic material found in every cell of a person’s body. They’d already sent semen samples from the Davis and Hellams murders to Lifecodes, a private lab in New York State that analyzed DNA for paternity tests.

At this point, no one in the U.S. had ever used DNA testing in a homicide investigation. But all of that was about to change.

THE PHONE CALL with Williams left Horgas even more confident that the same man had committed all five murders in Richmond and Arlington. And if that man was also the masked rapist, it meant the police had a very unusual lead: Nine eyewitnesses who had met a future serial killer.

Horgas began interviewing each of the nine rape survivors in Arlington, all of whom agreed to help. The similarities in the assaults were striking. Starting with the fourth victim, all of the women had been tied up with rope or cords from venetian blinds. The fifth victim had been locked in the trunk of a car that was subsequently set on fire, but she was able to kick her way out and escape. The last victim, who lived just six blocks away from Carolyn Hamm, had been attacked on Jan. 25, six hours after Hamm’s body was discovered.

On Dec. 28, Horgas flew to New York, then drove from the airport to the Lifecodes lab in Valhalla. With him, he carried samples from the Tucker and Hamm murders, as well as from several of the Arlington rapes. Lifecodes already had DNA samples from the Richmond murders. The question now was whether the crimes in both cities could be linked to the same genetic fingerprint. He was told the results would take at least six weeks.

In the interim, Horgas returned to Virginia and sought the expertise of FBI agents from the Behavioral Science Unit at Quantico, which had been creating profiles of serial killers since the early 1980s. On the morning of Dec. 29, agents Stephen Mardigan and Judson Ray drove north to Arlington through the falling snow to look at Horgas’ evidence.

It was dark by the time their meeting ended, but Horgas felt a surge of hope. Mardigan and Ray agreed with his theory.

The key to the whole case, the FBI agents said, was the location of the first rape in Arlington. The attacker would have committed his first assault in a place where he felt comfortable—most likely his own neighborhood. The agents also told

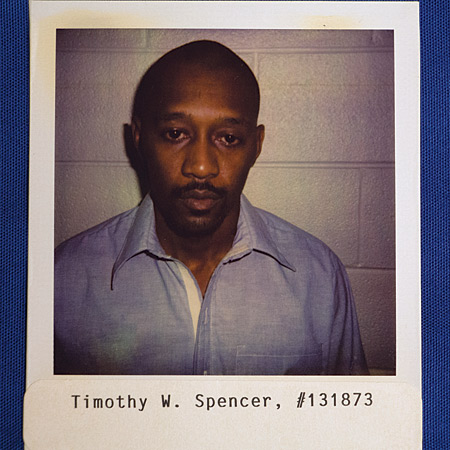

The serial killer in 1994, shortly before his execution

Horgas that, based on psychological profiling, such a perpetrator would only stop attacking women if he died or was locked up—meaning the dates on which the rapes and murders had occurred (and the gaps between) were telling. They advised Horgas to look for someone who had been arrested for burglary shortly after the Hamm murder in January 1984, and released just before the first Richmond murder in September 1987.

The next day, Horgas drove to South Oxford Street in Arlington and sat in his car. The rapist had abducted his first victim from a phone booth at the intersection of South Glebe Road and Second Street in June 1983, then parked on South Oxford Street and assaulted the woman in a nearby wooded lot.

Horgas began to search his mind. He’d been with the Arlington Police Department for 16 years. Who had he arrested near South Oxford Street?

Unable to jog his memory, he and his partner, Mike Hill, started pulling stacks of paper parole records, hunting for anyone whose record fit the arrest and release dates that had been outlined by the FBI agents. It was laborious work, in that each parole record had to be manually cross-checked with criminal records.

The first day, they went through 300 files. The second day, Horgas’ vision began to blur by lunchtime. Every so often, he drove to South Oxford Street and tried to remember. Then, four days after the paper chase began, a name popped into his mind: Timmy.

A neighborhood troublemaker he’d investigated a decade earlier for burglary, Timmy was rumored to have set fire to either a house or a car—similar to the way the masked rapist had torched a car with one of his victims tied up in the trunk. But what was Timmy’s last name?

Horgas continued sorting through records, drinking coffee and staring into space, sifting his memories for the last name. On Jan. 6, it finally surfaced: Timmy Spencer.

Rushing to the computer, he did a driver’s license check. When he searched for drivers born in 1962, a record for a Timothy W. Spencer appeared, current address: Richmond, Virginia.

With a date of birth in hand, Horgas then found Spencer’s police record. He’d been arrested on Jan. 29, 1984, for a burglary in Alexandria, four days after Carolyn Hamm’s body was found. He’d then been released to a halfway house on Richmond’s Southside on Sept. 4, 1987, two weeks before Debbie Davis was killed.

But that wasn’t all. Spencer’s mother lived less than a mile from the two murder sites in Arlington, and only 200 yards from the spot on Oxford Street where the first rape was committed.

“It was like putting a puzzle together,” Horgas remembers. “We ran the check on him, and lo and behold, everything just falls into place.”

THE RICHMOND POLICE agreed to put Spencer under surveillance, but after a week of watching the man do nothing suspicious, they decided to call it off.

By this time, Arlington prosecutor Helen Fahey was deeply involved in the case. Fahey (now retired in Arlington) had toured Susan Tucker’s house with Horgas shortly after the murder. She remembers the experience as “unsettling”—especially given that she was a single woman who lived alone, and had rented a town house in Fairlington that was the mirror image of the murdered woman’s home.

When Fahey heard that Richmond was calling off the surveillance, “she freaked out,” Horgas remembers. “She said, ‘There’s no damn way. We’ve got to do something.’ ”

Picture above: Former Arlington County prosecutor Helen Fahey

Pondering their options, Horgas came up with a solution. “What if,” he asked Fahey, “we ask for an indictment from the grand jury?” Unlike arrest warrants, grand jury indictments are difficult to challenge in court.

A few days after the Richmond police stopped watching Spencer, Horgas presented his evidence to a grand jury in Arlington. Indictment in hand, he roared down I-95 to Richmond, where, on Jan. 20 at 5:50 pm, he arrested Spencer at a halfway house on suspicion of burglary.

Heeding the advice of FBI profilers, the detective didn’t mention the murders or the rapes to the man he now had in custody. Instead, he hoped to use the long drive back to Arlington to get Spencer to talk. With no hard evidence, he knew there were only two ways to prove the case: Get Spencer to confess, or get him to volunteer a blood sample.

But Spencer said little during the drive north, even after Horgas tried to draw him out with news of his old neighborhood in Arlington. And he remained tight-lipped during the interrogation that followed. By 2 a.m., Horgas was ready to quit. He asked his prisoner one last time to submit to a blood test, saying it was needed to compare to some blood found on a broken window in a burglary case. To his astonishment, Spencer agreed.

Horgas was so surprised that he began to wonder if Spencer was actually innocent. With the science of DNA testing in its infancy, however, it’s likely that Spencer never realized that a blood test could be used to match a semen sample.

While Spencer remained in jail on the burglary charge, Horgas boarded a plane to New York, carrying the precious blood sample to Lifecodes. He was told the results would take at least six weeks, but he nevertheless proceeded to call Lisa Bennett, the technician in charge, nearly every day.

On March 16, Bennett called with the findings. Spencer’s DNA matched DNA left at the murders of Susan Tucker, Debbie Davis and Susan Hellams, as well as one of the Arlington rapes that had occurred four years earlier.

“When everything I did was finally deemed credible, [I] was ecstatic,” Horgas remembers. “Helen Fahey was standing by my desk, and she even gave me a kiss. On the cheek, now. She might not remember that, but I do.”

HORGAS KNEW he’d caught a serial killer, but the case wasn’t a done deal. Now Fahey had to convince a jury that Spencer was guilty—based on a science that most people had never even heard of.

“We were very, very nervous,” recalls Fahey, who would go on to serve as a federal prosecutor, appointed by President Bill Clinton in 1993. “This was a case where there was essentially DNA and almost nothing else. And when you were talking about capital murder, it was asking a lot of a jury to believe this new technology was sufficient to convict beyond a reasonable doubt.”

The science was so new, in fact, that the judge in the case, Benjamin Kendrick, had to hold a special hearing prior to Spencer’s court date to determine whether DNA evidence was legally admissible.

“It was very controversial at the time, in a lot of circles,” says Kendrick, 74, who lives in Arlington and still presides over a hundred cases a year as a circuit court judge. “A lot of people said it was hocus-pocus. I made the decision that it was reliable and was going to be admitted.”

On July 11, 1988, Timothy Wilson Spencer went on trial in Arlington for the murder of Susan Tucker. On July 16, after six hours of deliberation, the jury found Spencer guilty of murder. In the next phase of the trial, they imposed the death penalty.

“It was the first case in the country in which a person was found guilty of a capital murder and received the death penalty…based on DNA evidence,” Kendrick says.

THE DAY AFTER the trial ended, Horgas was once again sitting in Fahey’s office. But he wasn’t there to celebrate. He’d come to talk about exonerating David Vasquez, who was continuing to serve time for the murder of Carolyn Hamm.

Unfortunately, DNA testing would be no help in proving Vasquez’s innocence. After several years in storage, the samples from the Hamm murder were too degraded. Vasquez’s only hope was a pardon from the governor.

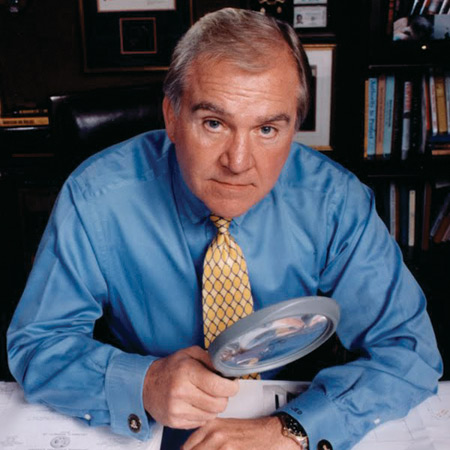

To make a case for Vasquez, Fahey formally requested the help of the FBI, including Special Agent John Douglas. Douglas had founded the FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit in the early 1980s after interviewing some of the most notorious serial killers in history, including David Berkowitz, Ted Bundy and Charles Manson, and noticing patterns in their behavior. (Now retired from the FBI, Douglas lives in Fredericksburg, where he writes about crime and works as an independent investigator. The character of Clarice Starling’s boss in The Silence of the Lambs is closely based on him.)

When Douglas agreed to help Fahey, it was the first time FBI profilers had ever been asked to help prove a suspect innocent. “I got involved, because one of the things that evolved at that time was linking cases together,” Douglas explains.

“What you look for is a signature. A signature is a ritual.” In the Spencer case, Douglas believed the unusual cord bindings constituted a unique signature in all five murders.

Citing this and other factors, FBI agent Stephen Mardigan drafted a 35-page report, along with a letter, which Douglas also signed, asking for Vasquez’s pardon. Fahey sent it, along with her own pardon petition, to Virginia Gov. Gerald Baliles in October 1988. On Jan. 4, 1989, Vasquez was released from prison, the first person in the U.S. to be exonerated—albeit indirectly—by DNA evidence.

IN 1988 AND 1989, Spencer was tried and convicted of the murders of Davis and Hellams in Richmond, and Cho in nearby Chesterfield. He was sentenced to death in each case.

Spencer was executed on April 27, 1994, at Greensville Correctional Center, after last-minute appeals for a stay of execution were denied by the U.S. Supreme Court. His attorneys had unsuccessfully petitioned to have the DNA samples that led to his conviction tested for a third time—even though a second test, conducted during the Davis trial, had confirmed the original DNA match.

Spencer was 32, and died without making a final statement. He was the last person executed by electric chair in Virginia before the General Assembly voted to allow inmates to die by lethal injection.

The case marked a watershed in law enforcement tactics. In 1989, Virginia became the first state to create a crime lab that could test DNA evidence. It also became the first state to set up a DNA database.

A year later, Patricia Cornwell’s first novel, Postmortem, was released, raising a few eyebrows among those familiar with the case. Cornwell had worked in the office of the chief medical examiner in Richmond in 1987, and was later criticized for the similarities between her plot and the Spencer murders.

Forensic DNA testing is what ultimately led to Spencer’s conviction. But there is one irony that lies in the prosaic paper records that Horgas combed through so tirelessly, searching for a man who had been paroled just before the 1987 killing spree began.

As it turns out, Horgas never would have found Spencer’s name in those records—because convicts released to halfway houses were not technically considered paroled. Fortunately, the detective’s memory didn’t fail him.

Pictured above: John Douglas

THE INNOCENCE PROJECT

With the advent of forensic DNA testing in the late 1980s, police discovered a powerful new tool for identifying criminals. But genetic fingerprinting soon proved to be equally effective at freeing the innocent.

To date, DNA testing has exonerated 329 people imprisoned for crimes they did not commit, including 20 inmates on death row. The Innocence Project, a nonprofit founded in 1992 by New York’s Benjamin Cardozo School of Law, has worked to free 179 of those prisoners.

Wrongful convictions can occur for a number of reasons, according to the nonprofit’s website (www.innocenceproject.org). In 75 percent of the cases it studied, an eyewitness pointed the finger at the wrong person. Roughly half of all wrongful convictions identified thus far also have involved mishandling of forensic evidence—from faulty blood tests to procedural errors in fingerprinting. (In one case, a suspect’s fingerprints were compared to his own test prints and not to the fingerprints found at the crime scene.)

In a fallible criminal justice system, even DNA testing has not proved foolproof. According to the Innocence Project, about 4 percent of exonerated prisoners were convicted as a result of improperly conducted DNA tests. For this reason, it’s not uncommon for defense attorneys in criminal proceedings to plea for retesting on behalf of their clients.

Arlington resident Laurie McClellan is a frequent contributor and writes Arlington Magazine’s Neighborhood Watch column.