Stand at the intersection of Columbia Pike and South Joyce Street today, and looking north, you’ll see white gravestones marching in orderly lines up a hillside. But from 1863 to 1900, this corner of Arlington National Cemetery was home to a settlement of former slaves known as Freedman’s Village.

Eight months before Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, slaves in the District of Columbia were freed by an act of Congress. Fugitive slaves fleeing the South soon flooded into the city, many of them moving into camps set up by the government. When smallpox swept through the overcrowded sites, however, Lt. Col. Elias M. Greene proposed that some of the freedmen could farm nearby land, and recommended the “pure country air” south of the Potomac.

That’s when authorities found an available tract of land equipped with a dose of payback: the Arlington estate of Robert E. Lee and his wife, Mary Custis Lee, which had been seized by the Union early in the war.

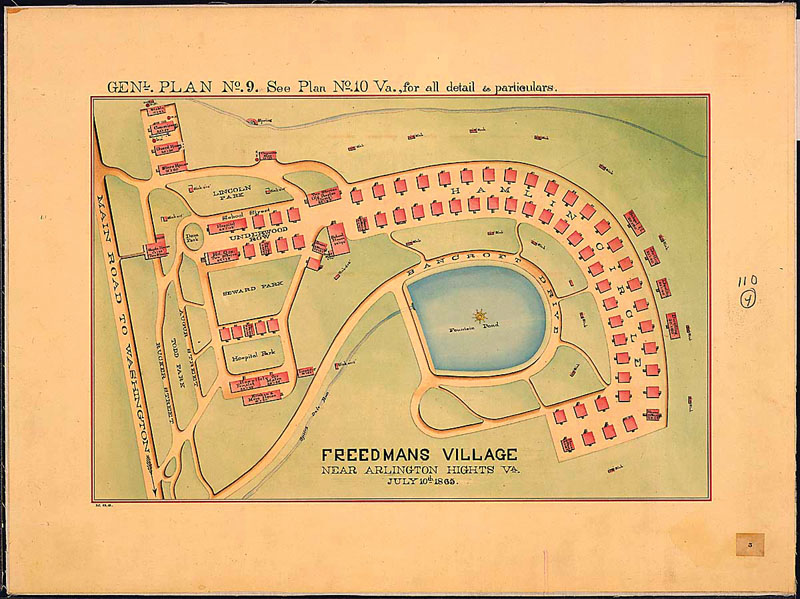

Although no one knows exactly where Freedman’s Village stood, it’s believed that the buildings—which included some 50 houses curving around a central pond—were located in what are today sections 8, 47 and 25 of Arlington National Cemetery, along Eisenhower Drive. The first hundred residents moved into the settlement in June 1863, but the population eventually swelled to several thousand.

In addition to the houses, the village included a school, a hospital and eventually, several churches. An 1864 article in Harper’s Weekly praised the settlement, noting, “The principal street is over a quarter of a mile long, and the place presents a clean and prosperous appearance at all times.” While children attended school, adults farmed or trained to become shoemakers, blacksmiths or wheelwrights. Famed abolitionist and preacher Sojourner Truth lived at Freedman’s Village for about a year, counseling its residents and finding work for the unemployed.

Though the village was intended to serve as a temporary home where former slaves could learn new job skills, many people in Freedman’s Village grew attached to the community and stayed. But conflicts often arose between the residents and the authorities who ran the camp—first the Army, which originally set up the village; and later, the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands, which took over its administration in 1865. Residents who earned $10 per month on government farms resented having to pay authorities the $5 per month that they were charged as a “contraband fund tax” to support the village. (Slaves who escaped to the Union were known as “contraband of war,” a term that lived on after the Civil War.)

In the end, however, it was rising land values, not internal tensions, that led to the village’s demise. In the late 1890s, real estate developers began touting land in what is now Arlington County, luring Washington workers with promises of “quiet and repose from the stir and bustle and noise” of the city.

Some speculators hoped to purchase the land that Freedman’s Village sat on from the government, while civic groups advocated turning it into a public park.

Amid mounting public pressure, in 1900, Congress offered the people of Freedman’s Village $75,000, partly as a refund of the contested contraband fund tax. The settlement was divided among the residents, and the village was torn down.

Instead of scattering, many of the villagers simply moved to other parts of the county. They settled the neighborhoods of Nauck, High View Park–Halls Hill, and Butler-Holmes (now Penrose), places that retain a direct link to Arlington’s Civil War past.