The Mount Olivet Cemetery in Frederick, Maryland, seems an unlikely spot for a vocabulary lesson, especially after dark. But that’s where I learned about taphophobia—the fear of being buried alive—from historian Chris Hough, who leads nighttime tours of the cemetery with a swinging lantern in hand. During the Victorian era, Hough explains, people were sometimes buried with a cord inside their caskets as a safeguard in case they weren’t really dead. If they happened to wake up, they could pull on the cord to ring a small bell hanging above their grave. The practice may have given rise to the expressions “dead ringer” and “saved by the bell.”

Old cemeteries are steeped in history of all kinds, from the colorful to the solemn—especially in Maryland and Virginia, where you can find the final resting places of presidents and spies, war heroes and assassins. And fall is prime time for visiting, as many cemeteries offer special tours around Halloween.

Christ Church Cemetery

Alexandria, Virginia

Although a thousand people lie buried around Christ Church, only a few dozen tombstones stand in the historic graveyard today, beckoning passersby to read their fading letters. Why the discrepancy? Many of those buried here could not afford a marker. It’s also believed that some gravestones were stolen and used to pave the walkways of houses in Old Town.

The tombstones make for fascinating, if brief, reading. George Mumford’s slate marker states that he died in 1773; his birthplace is given as “New London in the Colony of Connecticut.” A macabre poem marks the final resting place of Sarah Wrenn, who died in 1792: “All you who come my grave to see, As I am now you soon will be. Prepare and turn to God in time, For I was taken in my prime.”

Christ Church in Alexandria

The headstone for actress Anne Warren, who died only a decade later in 1808, strikes a much less dour note. Part of the long inscription reads, “By her loss the American stage has been deprived of one of its Brightest Ornaments. The unrivalled excellence of theatrical talents was surpassed by the mighty virtues and accomplishments which adorned her private life.”

While you’re visiting the graveyard, step inside the church itself for a quick tour. Both George Washington and Robert E. Lee attended services here, and tour docents will let you sit in George Washington’s own box pew.

Plan Your Visit

Christ Church Cemetery

118 N. Washington St., Alexandria

703-836-5258

historicchristchurch.org

Open during daylight hours, with free tours of the historic church available Monday-Saturday, 9 a.m.-4 p.m., and Sunday, 2-4 p.m. Gift shop is open Tuesday-Saturday, 10 a.m.-4 p.m., and Sunday, 9 a.m.-noon. Restrooms are in the parish house.

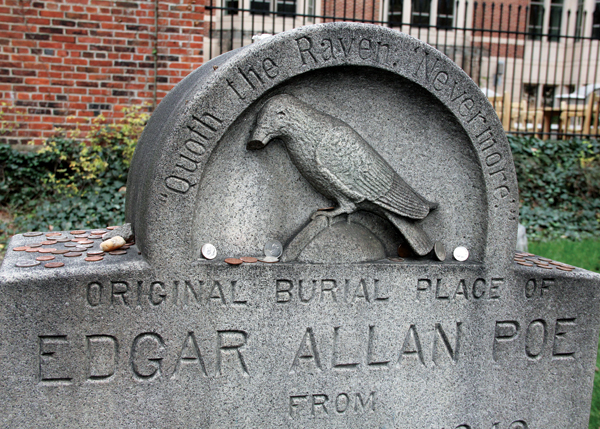

The famed poet’s grave

Westminster Burying Ground

Baltimore, Maryland

Once upon a midnight in 1949 (history does not record whether it was dreary or not), a mysterious stranger left three roses and a bottle of cognac on the grave of Edgar Allan Poe in downtown Baltimore. The stranger, who came to be known as the “Poe Toaster,” visited the grave every year at midnight on Poe’s birthday until 1993. His annual appearance became a spectating ritual for city natives, who showed up in crowds to watch, but never disturbed him or learned his identity.

Poe’s elaborate marble monument was paid for partly by local schoolchildren who gave pennies to a fundraising campaign known as “Pennies for Poe.” Pennies are still left on the grave to this day, which is also the final resting place of Poe’s wife (and first cousin), Virginia, and his beloved aunt and mother-in-law, Maria Clemm.

Westminster Burying Ground

Alert fans may notice a glaring typo in the monument’s inscription, which gives Poe’s birth date as Jan. 20 (his actual birthday was Jan. 19). American poet Walt Whitman, who actually met Poe once, attended the monument’s dedication ceremony in 1875. A small headstone at the rear of the cemetery marks the spot where Poe was originally buried.

Although Poe is the star of this city cemetery founded in 1787—once known as Baltimore’s most exclusive burying place—there’s plenty more to see in the churchyard packed with obelisks, Egyptian Revival tombs and even a large pyramid. James McHenry, a signer of the U.S. Constitution (and for whom Fort McHenry is named), is buried here, as are veterans of the American Revolution and the War of 1812.

One oddity of the burying ground is that the church was built some 60 years after the graveyard was established. To avoid disturbing the graves, the floor of the church was built several feet above them on pillars, creating catacombs.

Plan Your Visit

Westminster Burying Ground

519 W. Fayette St., Baltimore, Maryland

410-706-2072

law.umaryland.edu/westminster

Grounds open daily, 8 a.m.-dusk, with historic markers and plaques providing a self-guided tour. Visits to the catacombs are via guided tours on the first and third Friday (at 6:30 p.m.) and Saturday (at 10 a.m.) of each month, April to November. Reservations are required, and at least 15 people need to sign up in order for a tour to take place. Fee is $5 for adults; $3 for children 12 and under, and seniors 60 and older.

The annual Halloween tour on Oct. 31, 6-9 p.m. ($5 for adults; $3 for children) is a Baltimore tradition, featuring a walk through Westminster Hall, eerie organ music, historical characters and presentations of Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart.” See website for details.

The Renwick Chapel at Oak Hill (above)

Oak Hill Cemetery

Washington, D.C.

The tombstones of Georgetown’s Oak Hill Cemetery read like a who’s who of early Washington. That’s no accident. When philanthropist and art collector William Corcoran founded Oak Hill in 1849, a movement to create garden-like cemeteries with winding paths and expansive views was sweeping the country, and Oak Hill soon became a fashionable place to be buried. James Renwick, architect of the Smithsonian Castle, was even hired to design the cemetery’s miniature Gothic chapel.

Joseph E. Willard’s storied grave marker

When Abraham and Mary Lincoln’s son Willie died of typhoid in 1862, his prayer service was held in the chapel and his casket was temporarily placed in the Carroll family mausoleum at Oak Hill (William Carroll was then clerk of the U.S. Supreme Court) before it was returned to Springfield, Illinois.

During the Civil War, Lincoln would occasionally sit in a rocking chair in front of Willie’s resting place, looking out over Rock Creek below. (Ironically, Jefferson Davis’ son was buried in Oak Hill around the same time, although Davis was unable to visit during the war.) Other Civil War notables interred here include Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and attorney Frederick Aiken, who defended Mary Surratt at her

trial for aiding and abetting in Lincoln’s assassination. Aiken’s tombstone is inscribed with the elegant opening words of his defense. (The 2011 film The Conspirator focused on Aiken’s role in the trial, with James McAvoy starring as the young attorney.)

The Van Ness Mausoleum at Oak Hill (below)

The most romantic story in Oak Hill may belong to Union Gen. Joseph Willard and his wife, Antonia Ford Willard, a Confederate spy. It’s said that she and the general fell in love while he was escorting her to prison. The two were married in 1864, after which Willard returned to the family business, D.C.’s Willard Hotel.

Their son, Joseph E. Willard, served as U.S. ambassador to Spain and is also buried in Oak Hill, where his grave is marked with an Augustus Saint-Gaudens sculpture of an angel. The artwork, valued at over $100,000, was stolen from the cemetery in 1985. After an article about the theft appeared in The New York Times, the sculpture was recovered by police and returned in 1986.

Plan Your Visit

Oak Hill Cemetery

3001 R St. NW, Washington, D.C.

202-337-2835

oakhillcemeterydc.org

Open Saturdays, 11 a.m.-4 p.m., Sundays 1-4 p.m., and weekdays 9 a.m.-4:30 p.m. Cars allowed weekdays only (no holidays) on cemetery grounds. A large printed map (usually available at the entrance for $3) is handy for touring the cemetery, although you can also find a map on the website. To find the restrooms, turn left at the office and walk to the end of the staff building. There are no formal tours, but the historic chapel is often open to visitors on weekends.

The Monument to the Confederate War Dead at Hollywood Cemetery

Hollywood Cemetery

Richmond, Virginia

You could be forgiven for mistaking Hollywood Cemetery—so named for the holly trees dotting its landscape—for a garden, a park or an outdoor art museum. The tour guides here emphasize that it’s designed to work as all three. With its rich history and scenic setting above the rapids of the James River near downtown Richmond, Hollywood attracts hordes of visitors and walkers, and is said to be the second-most-visited cemetery in the country, right behind Arlington National Cemetery.

The walking tour lasts about two hours and covers art, architecture and history, but you can also tour the cemetery via car, Segway or trolley. Flowers bloom everywhere in the spring and summer—it takes a crew of 30 volunteers just to tend the heirloom rosebushes. Hollywood is home to two U.S. presidents, James Monroe and John Tyler, as well as Confederate president Jefferson Davis.

Other highlights include the Monument to the Confederate War Dead, a 90-foot pyramid made of huge granite blocks, and the graves of 22 Confederate generals, including J.E.B. Stuart.

Every tour stops at the grave of 2-year-old Florence Rees, who died of scarlet fever in 1862. Rees’ grave is guarded by a life-size statue of a Newfoundland dog molded from cast iron. It’s believed the girl’s grandfather moved the black dog to Hollywood after the Civil War broke out, to prevent it from being melted down for bullets.

Plan Your Visit

Hollywood Cemetery

412 S. Cherry St., Richmond

804-648-8501

tour.hollywoodcemetery.org

Open daily, 8 a.m.-5 p.m. (6 p.m. during daylight savings time). Pick up a map for $1 at the office (open weekdays, 8:30 a.m.-4:30 p.m.) or use the interactive map online. Restrooms are located outside the office building. If you’d like to drive through the cemetery, blue lines painted on the roadways mark out an easy-to-follow historic tour for cars.

Guided tours are also available. From April to October, the Valentine history museum offers walking tours ($15), Monday-Saturday at 10 a.m. In November, tours are offered Saturday at 10 a.m. and Sunday at 2 p.m. The walking tour lasts about two hours and covers two miles. You can also tour the cemetery via electric car, trolley or Segway. See website for details.

Mount Olivet Cemetery

Frederick, Maryland

Mount Olivet Cemetery could be called a peaceful place, except for the button. The button is located on a historical marker in front of Francis Scott Key’s grave, and every time a visitor pushes it, a booming rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner” blasts though the cemetery at top volume.

Key is definitely the main attraction here and you can’t miss his grave. It’s marked by a 16-foot column, which is then topped by a nine-foot statue of Key waving his hat and pointing at the nearby American flag that has flown continuously since 1949. Key was born in Frederick County and began his law practice in Frederick in 1801; although he was originally buried in Baltimore, civic leaders persuaded his granddaughter to reinter him at Mount Olivet.

A monument to Francis Scott Key at Mount Olivet Cemetery

In the fall, you can tour Mount Olivet after dark with a guide toting a spooky lantern. The informative historic tour stops at Confederate Row, where soldiers from the nearby Battle of Antietam are buried, and at the grave of local patriot Barbara Fritchie, whose encounter with Stonewall Jackson during the Civil War was immortalized in the poem by John Greenleaf Whittier. In the poem, Fritchie defies Confederate soldiers who are firing at the American flag she’s hung from her window, shouting “Shoot, if you must, this old gray head, but spare your country’s flag!” Historians have called the story’s accuracy into doubt, but it’s still a rousing line to contemplate—especially if anyone has pushed the “Star-Spangled Banner” button.

Plan Your Visit

Mount Olivet Cemetery

515 S. Market St., Frederick, Maryland

301-662-1164

mountolivetcemeteryinc.com

Open during daylight hours, with free maps and restrooms available near the Market Street entrance. Cars are allowed at all times. To visit after dark, Maryland Ghost Tours offers a 90-minute, 1-mile candlelight walking tour in October and early November that touches on famous residents, grave robbing and a particular piece of trivia from the game show Jeopardy!. Fee is $10 for adults; $8 for seniors/active military; $5 for kids 7 to 12 (not recommended for children 6 and younger). Visit marylandghosttours.com for details, or call 301-668-8922.

Laurie McClellan is working on a book about historic cemeteries in and around Washington, D.C. Find her at www.lauriemcclellan.com.