Sara’s experience is not an anomaly. A study released in September of 2011 by the Arlington Partnership for Children, Youth & Families reported that nearly 28 percent of Arlington eighth-graders and one in five high school sophomores said they had been bullied in the past year.

Nationally, 33 percent of girls report being bullied, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

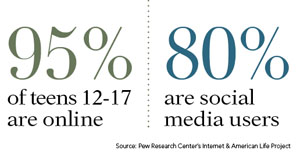

And although bullying in the old days often involved playground scuffles and stolen bikes, today’s harassment is much more cerebral and technology-driven. In a 2007 study by the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project, more than a third of teenagers who use the Internet said they had been the target of online taunts, from threatening messages, vicious rumors, and private emails or texts forwarded without their permission to embarrassing pictures posted on the Internet for all to see.

In this world, the perpetrators are often females who prey on other females. Among the teen participants in the Pew study, 38 percent of girls reported being bullied online, compared with 26 percent of boys. That number was even higher—41 percent—among girls between the ages of 15 and 17. Hate lists, snarky texts and mean-spirited social media posts are weapons that many teenage girls have learned to use with heartbreaking adeptness.

“It’s been hell,” says Patti, an Arlington mom who feels torn between the parental instinct to protect her girls and the need to let them fight their own battles. She and her husband have spent $130,000 out of pocket on counseling to help their daughters cope, she says. Their oldest is in college now, but for the younger one, “there’s been no place she could go unmolested. Not church, not the grocery store, not the mall.”

One fellow student told her daughter, “Why don’t you just kill yourself and get out of everyone’s life?”

Though academic pressures are rampant in area schools, “relationships are the ‘class’ that girls are paying the most attention to,” observes Rachel Simmons, author of the best-selling seminal works Odd Girl Out: The Hidden Culture of Aggression in Girls and The Curse of the Good Girl: Raising Authentic Girls With Courage and Confidence.

A childhood victim of bullying herself, Simmons, now a leadership development consultant for the Center for Work and Life at Smith College in Northampton, Mass., explains relational aggression as “the use of friendship as a weapon.” An aggressor will often form covert alliances and set out to isolate her victim by undermining both her friendships and status. Sometimes these attacks are launched without cause or provocation. Often, as in Sara’s case, the aggressor is someone who was once a friend.

Fear often prevents bystanders from stepping forward to defend the girl who has been arbitrarily singled out. A Pew survey of students between the ages of 12 and 17, released in November 2011, found that 90 percent of teens who had witnessed incidents of online cruelty admitted to ignoring the behavior.

“Girls often won’t differentiate themselves in front of their peers,” says Cindy, a mom in Falls Church. “They won’t step up to tell what’s happening or comfort a victim.”