Ordinary citizens, they’ve made a habit of testing their physical strength, stamina and mental toughness in ways that are anything but ordinary.

Michael Wardian

Ultramarathons

Michael Wardian’s not crazy. He’s just trying to figure out how far and how fast he can run. The verdict is still out.

Wardian played sports in high school and college, but didn’t take up distance running until he graduated in 1996 from Michigan State, where he played Division I lacrosse.

During his junior year, he visited a friend whose mom ran the Boston Marathon. “I thought it sounded really cool,” he remembers. “She gave me a packet on how to train for a marathon, so I just followed the instructions.” Simple, right?

He ran his first marathon (the Marine Corps) in the fall of ’96, finishing in 3 hours, 8 minutes and qualifying for Boston. Looking back, he laughs at his formerly unseasoned self. “I ran in lacrosse shorts, didn’t use any gels and barely stopped for water,” he recalls. In Boston the following spring, he pulled a 2:54.

Not long after, a friend postulated that no one could possibly run three marathons in a month. Wardian thought, why not? In 1997, he ran Chicago, Marine Corps and New York, all within four weeks.

Now 38, he races 40-50 times a year. He’s run two marathons pushing a stroller (breaking one course record in the process), taken home a silver medal for the 100K distance for Team USA, established a Guinness World Record for fastest marathon dressed as a superhero (he was Spiderman) and finished third at Badwater, arguably one of the toughest footraces in the world, stretching 135 miles from Death Valley to Mt. Whitney, Calif., in the middle of July. Last year, he set two personal best times: a 2:17 marathon and a 30:24 10K.

As it turns out, Wardian is both exceedingly normal and terrifically humble. He works fulltime as an international shipbroker at a small firm in Dupont Circle, finding cargo—primarily humanitarian food aid—for ocean carriers. “If you ever see those sad commercials on TV, that’s what we do,” he explains. “We help get those kids food.”

In addition to running upwards of 100 miles a week on treadmill, trails, track and road, he bikes to work from his home in Arlington Forest, where he lives with his wife, Jennifer, and two sons, Pierce, 5, and Grant, 3.

“Mike’s been running as long as I’ve known him—for several hours a day. I knew what I was getting into,” says his wife, who runs the occasional 5K with her husband, but mostly supports him by making sure he remembers to pack his running shoes.

Last November, the couple discovered that their younger son, Grant, has epilepsy. Still in the process of figuring out what triggers his seizures, they now take turns waking up every two hours during the night to check on him, which has taken a toll. For Wardian, it’s meant sticking closer to home and significantly cutting back his usual race schedule. Still, one run that’s on his must list for this year is South Africa’s elite Comrades ultramarathon, a 56-mile race that he finished in 11th place last year. This time he’s hoping to break the Top 10.

”It’s really just about seeing what I’m capable of, what I can endure,” he explains. “There are times when you know it’s not going to be fun, but if you can rally around that feeling and do it anyway, it’s so empowering. I really love the feeling of knowing there’s going to be discomfort and sacrifice, but that if you can reach the finish line and achieve your goals, it’s all going to be worth it.”

Erik Franklin

Erik Franklin

Distance swimming

Every June, some 700 intrepid swimmers plunge into the Chesapeake’s murky waters for the Great Chesapeake Bay Swim, a grueling 4.4-mile race against the winds, currents and chilly temperatures of the open water underneath the Bay Bridge.

“If you get blown out from beneath the bridge, they yank you from it,” explains repeat competitor Erik Franklin, noting that organizers have sometimes pulled more than half of the racers out of the water for safety reasons.

But not him. From 2006 to 2010, Franklin completed five consecutive Bay swims, scoring a couple of second places in his age group. In 2007 he placed 14th overall.

A competitive freestyler since age 6, Franklin attended Brown University and swam all through college. By the time he reached his mid-30s, he was logging 25,000 yards (think 250 football fields) per week—a routine that included morning sessions at the pool before work, plus a marathon 3 ½-hour, 9,000-yard workout every weekend.

But when he injured both shoulders two years ago (sustaining a cartilage tear on the right, from swimming; followed by a collarbone fracture, torn ligaments and rotator cuff damage on the left, after a skiing accident), a new reality set in.

“The question became, ‘How do I do what I did before, understanding that I can’t do it the same way?’” says Franklin, who works in technical sales for Microsoft and lives in Waycroft-Woodlawn with his wife, Sara, and two daughters.

Rehab was a slow and humbling process, starting with running, biking and using free weights to restore range of motion and flexibility. “My buddy at the gym had to spot me with my 10-pound weights,” he says. “I didn’t touch the water for months.” But patience and persistence ultimately prevailed.

Now 40 and swimming again, Franklin is steadily regaining the endurance he lost while injured. He swims three or four times a week at Washington-Lee (where his daughters, Grace, 9, and Caroline, 7, will eventually go to high school), training with the same masters team he’s been with for 10 years. Its members range in age from 23 to over 50. They meet at the pool at 5:30 a.m.

When traveling for work, he scouts out and trains with masters teams in other cities to avoid lapses in his routine.

And, slowly but surely, he’s returning to the race circuit, starting with a few modest, one- and two-mile races this summer. His expectations are different now, but his love of the sport and its culture hasn’t changed.

“It’s not just the competition; it’s also the charities [these races] benefit,” says Franklin, who has raised more than $15,000 for good causes over the years. “When you’re getting up early or staying up late to train, it helps to know it’s not just about your personal goals. It’s about something bigger than you.”

Kris Winkler

Kris Winkler

Tough Mudder

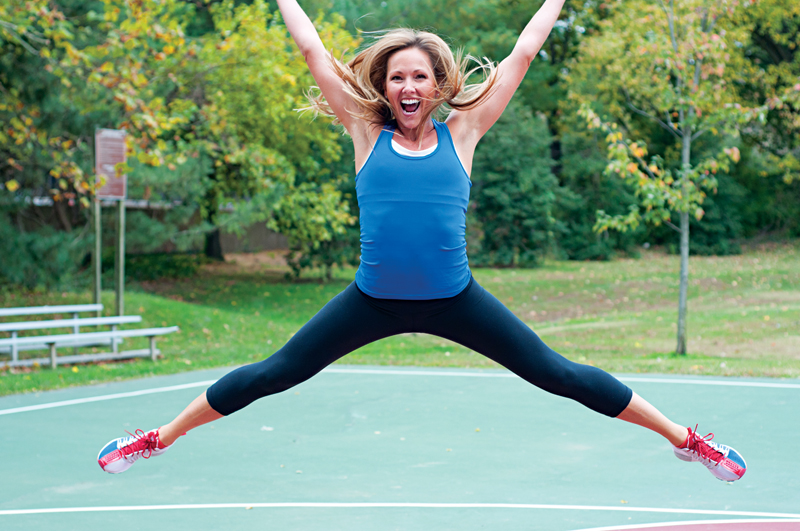

Kris Winkler is the athlete next door. A senior manager at Rockville, Md.-based MBL Technologies, she lives in Fairlington, walks her dog, Max, every morning, tries a new restaurant each week and celebrated her 45th birthday this February.

She’s also a badass.

Last year she hauled herself up a 20-foot-long rope only to plunge back down into frigid water, swung across an inverted V of monkey bars—some greased—crawled on rocks through tunnels partially submerged in water and filled with people, and then ran through a field of live wires. And that was just her first Tough Mudder.

A “Tough Mudder” is a 10- to 12-mile race in which groups of eight to 10 people stampede through a military-style obstacle course designed to test strength, stamina and mental reserves. Prepping for the race requires a physically grueling cross-training regimen, including flipping tires, swinging kettlebells and scaling walls. To sharpen her focus for the first event, Winkler also practiced meditation and drumming with trainer Warren Bloom, who emphasizes whole-body-and-mind wellness. Now she’s training for her second.

Winkler has always been a strong, natural athlete, although from fifth to seventh grade, she spent 23 hours a day in a chin-to-hip body brace to correct a degenerative spine disease. “After something like that, you just don’t let things stop you,” she says. “It makes you who you are.”

A positive person, Winkler regards each day as an opportunity to push her personal limits and try something new. (“That’s what drew me to her,” says her boyfriend, Bernie Braun.) Looking for a challenge beyond 10Ks and half marathons is what led her to the Tough Mudder; the opportunity to build camaraderie and serve as a role model for her niece and nephew sweetened the deal.

“The biggest commitment,” she says, “is to your teammates. You commit to be in shape, to face your fears. Jumping off that platform into 41-degree water was my biggest fear. I was terrified of the cold. But I knew if I could get through that, I could do anything.”

Paula Pettavino

Paula Pettavino

Pilates, Trapeze and Aerial silks

Earthbound exercise is all well and good. But a year and a half ago, Pilates instructor Paula Pettavino left the ground and took to the air.

For many of her current workouts, she now hangs, sometimes upside down, from long strips of fabric or a trapeze bar suspended from the ceiling, holding impossible extensions.

Her exercise regimen wasn’t always so acrobatic. A former politics professor at American and Marymount universities, Pettavino ran, biked and took cardio classes to stay in shape until a friend invited her to a Pilates class about six years ago. She was quickly intrigued by the precision required in each movement and the strength and flexibility she gained.

Parlaying that strength into aerial silks and static trapeze was a fairly natural progression, says the 62-year-old, who now takes weekly lessons with Arachne Aerial Arts, a performance and education group that teaches at Joe’s Movement Emporium in Mount Rainier, Md.

In January she traveled to Vermont for a workshop with the New England Center for Circus Arts, which trains performers for Cirque du Soleil.

When she’s not airborne, Pettavino runs her own studio, the Pilates Ab-Lab, from her home in Riverwood near Windy Run Park. In addition to teaching about 12 clients a week, she takes Pilates lessons from fellow instructor Isabella Giuliano, who also lives in Arlington. Giuliano was certified by Romana Kryzanowska, one of the last surviving students of Pilates founder Joseph Pilates.

“Pilates is all about alignment, moving properly as your muscles support your skeletal structure,” Pettavino explains. “Clients say they sit down in their cars and have to adjust the rearview mirror because they’re sitting up taller.” It also provides the gymnastic flexibility and discipline needed for aerial arts, she adds.

The irony is that Pettavino once had a fear of heights. It’s a phobia she has since overcome.

“I thought with age I’d get more fearful,” she says. “Instead, I’m doing more and more things. I can do that by getting stronger and stronger. Personally, I feel better than ever.”

Scott Thompson

Scott Thompson

Cyclo-Cross racing

Take the bike off-road, throw in some steep hills, ditches and obstacles, and smear on copious amounts of grass and mud.

What you get is a cyclo-cross race.

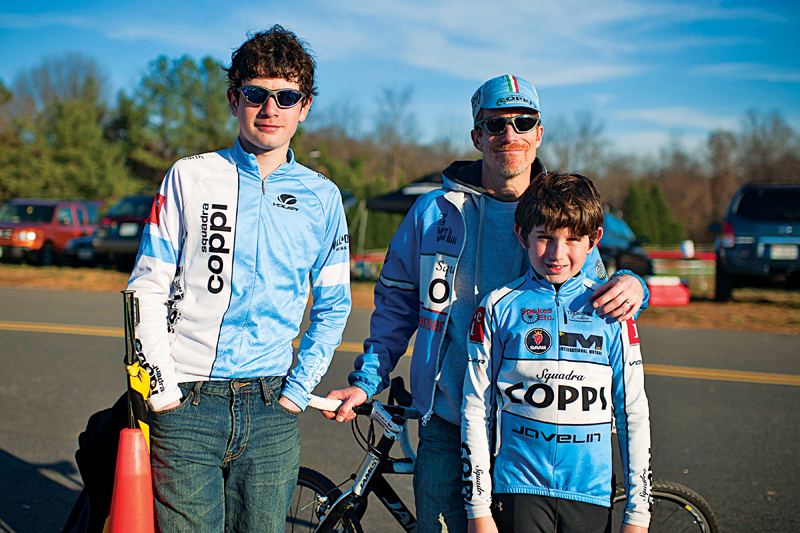

Scott Thompson says there’s no better way to spend a blistering hour with his heart rate accelerated above 180 beats per minute. A road-bike racer in college, he took up cycling again about 10 years ago. Friends who rode cyclo-cross invited him to an event and he was hooked.

“I immediately loved it,” says Thompson, 45, a communications lawyer with Davis Wright Tremaine in Washington, D.C., who lives with his wife, Loren, and two sons in Leeway Heights, near Westover. “It was the most fun I’d had racing my bike. Ever.”

Compared to the smooth asphalt courses of traditional road races, cyclo-cross is the Thunderdome. Riders must dismount at high speeds to run up or down slopes, jump over 40-centimeter-high hurdles, and clear sandpits or stairs, all the while carrying their bikes. The courses—rugged paths that are a mere three to six meters wide—are typically loops measuring about three kilometers, which the racers circle multiple times.

“It challenges you both physically and mentally, and there’s a significant amount of skill involved,” Thompson says. “You might be a super-strong triathlete, but this event requires you to maintain speed, combined with the skill of handling the bike on inappropriate surfaces.”

In Thompson’s case, cyclo-cross is also a medium for father-son bonding. He and his younger son, Liam, who starts sixth grade at Swanson Middle School this fall, belong to Squadra Coppi, an Arlington bicycle racing team. Liam did six races last year.

His older son, Jake, a rising junior at Yorktown High School (who started racing at age 9) won the top spot in his 15-18 age group last year and placed sixth in a beginner-level men’s race. Jake is now ranked 11th in the country for his age group and rides for an elite junior team based in Herndon.

During the week, Thompson often bikes to work, stopping at Hains Point to get some extra miles in.

Races take up most weekends in the fall, he says. Some are close by—at places like Lake Fairfax Park in Reston or Rockburn Branch Park in Howard County, Md.—but the family is also known to travel farther afield for events such as the Luray Caverns CX in Luray, Va., and the state championships in Charlottesville.

“We leave at the crack of dawn and race all day,” Thompson says. “It gives us some great times together.”

Sheila Cordaro

Sheila Cordaro

Boot Camps and Ragnar Relays

On any given day, Sheila Cordaro does about 300 crunches, 100 lunges and 50 push-ups, barely breaking a sweat as she barks commands to participants in her boot camp sessions.

But those reps “don’t count” as part of her own workout, she says. In addition to teaching roughly four classes per day, Cordaro adheres to a regimen that includes running (she mixes tempo runs on the track at Washington-Lee High School with longer jogs on the Custis Trail), yoga, and cardio and core strength training—a box she checks off by hitting up the fitness classes taught by other instructors at her company, FIT 4 MOMs.

As a result, the 41-year-old mother of two is pretty much always primed for a hard-core challenge, be it a triathlon (she completed her first eight years ago when her first child was just 3 months old), the Boston Marathon (which she ran this past April) or her latest obsession: Ragnar Relays.

Named after a Norse Viking from the 9th century, Ragnar is a 200-mile overnight, all-terrain relay race completed by a team of six to 12 runners. Over the course of two days and one night, each team member runs three legs of varying distances. Some legs are run in broad daylight; others are in pitch-dark.

While training for her first Ragnar two years ago, Cordaro was often out the door of her home in Waycroft-Woodlawn at 4:45 a.m. to sneak in a run before her 6 a.m. class. “I had to work it in that way,” says the former personnel recruiter, who left the corporate world in 2003 to start her own fitness business. “We wanted to train our bodies to be able to run at any time of the day or night.”

Still, no amount of training prepared her for what ultimately happened during the race. She became seriously ill about three miles into her first leg (a 17-mile stretch) but refused to stop, finishing the run utterly dehydrated and depleted.

Unwilling to concede defeat, she declined treatment from paramedics. “I finally was able to eat a very dry baked potato. That’s what fueled me for my next 11-mile stretch…at 3 a.m.,” she says. “That part of the race was like being in The Blair Witch Project. It was through the woods and up a mountain while wearing a headlamp. At one point I jumped over a snake.”

Giving up was never an option, Cordaro says matter-of-factly, citing what seems to be a family mantra. Her husband, Nick, is an award-winning triathlete, and her kids, Jaden, 8, and Joey, 6, who attend Arlington Traditional School, are dedicated participants in her company’s latest spin-off venture, FIT 4 KIDZ.

Next up: the Adirondack Ragnar Ultra, which Cordaro plans to conquer in September.

“I crash every night,” she says, “but if I were tired during the day I probably wouldn’t admit it. Once you admit it, you’ve owned it.”

Mark Dickson

Mark Dickson

IronMan Triathlons

By day, Mark Dickson is a mild-mannered math teacher at the H.B. Woodlawn School. But on evenings and weekends, he transforms into an Ironman.

“I got tired of simply running,” explains the veteran of several marathons, who completed his first Ironman World Championship in Hawaii in 1997. “It’s more fun to mix it up.”

Dickson competed in a second full Ironman in Hawaii in 2004, but lately he’s been “taking it easy” by sticking to local Half Ironman triathlons—events in June and September that involve a mere 1.2 miles of swimming, 56 miles of cycling and 13.1 miles of running.

A varsity athlete in high school and college, Dickson played soccer and softball in his 20s. But when he and his wife, Chris McKelvey, a rocket scientist at Orbital Sciences Corp., learned that baby No. 2 was twins, he realized he needed a workout routine with more flexibility. That’s when he turned to solo competitions.

These days his weekly regimen includes two one-to-three-mile swims at the Yorktown High School pool, 25 miles of running on the W&OD Trail, and one or two weight-lifting sessions, plus some stationary bike rides in his basement. On Saturdays, his wife watches their three kids while he takes a 60-mile bike ride or runs 20 miles.

“You definitely have to enjoy the training to make it worthwhile,” says the Highland Park resident. Setting achievable goals—such as improving his flip turn or including interval training—makes the time between races rewarding, he says.

Now 48, Dickson hopes to enter the famed Hawaiian Ironman once more by lottery. He won’t qualify on his times alone, he explains, so getting in is half the battle.

From that point on, he’ll rely on sheer grit and the company of others to make it to the finish line. “No matter how fast or slow you are, there are always people at your ability,” he says. “You actually get to socialize too, particularly on the run when everyone’s on their last leg.”

Over the years, Dickson has acquired a few admirers. His determination has inspired several students at Woodlawn to train for a Half Ironman for their senior projects. And, last summer, his own three children completed the Manassas Mini Tri, a short-distance triathlon for newbies, which includes swimming in a pool rather than open water. But he isn’t letting it go to his head.

“I consider myself a very average athlete,” Dickson says modestly. “Anybody who’s healthy and injury-free can do this.”

Anyone?

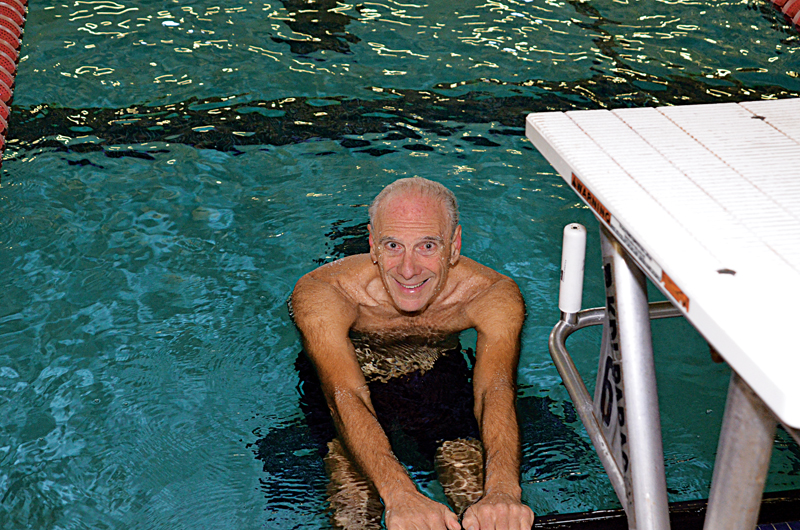

Herb Levitan

Herb Levitan

Senior Olympics

Herb Levitan can make 22 out of 25 consecutive basketball free throws. He can swim a 100-meter freestyle in 1 minute, 41 seconds. And those are only a couple of the bragging rights for the Boulevard Manor resident.

Last year, Levitan competed in 23 events in the Northern Virginia Senior Olympics—from free throws to pickleball. He won seven gold, three silver and eight bronze medals in his age group.

At the National Senior Games in 2009, which require state qualification and draw thousands of competitors, he won sixth- and eighth-place ribbons for swimming. That same year (and the year after) he placed second in his age group in the Nation’s Triathlon in D.C., finishing the grueling tripartite course in 3:21.

He is 73.

“I feel convinced that one can continue to learn at all ages, learning what your body can do, but also intellectually,” says the former professor of neuroscience at the University of Maryland, who also worked as a program director for the National Science Foundation before his retirement in 2004. He now studies classical guitar (because he felt “musically illiterate”) and volunteers for both Capital Hospice and the Northern Virginia Senior Olympics steering committee.

Levitan works out two to four hours a day with a varied routine that includes spinning, swimming, cycling on the W&OD Trail and yoga-style stretching. His wife and workout partner, Karen, teaches tai chi for Arlington County.

Lately, he’s been observing long jumpers in action in local competitions. He plans to try that event next.

But his ultimate dream is to swim at the National Senior Games with his daughter Danielle, who will be eligible in seven years when she turns 50.

“I’m out to find things that I’ve never done before,” Levitan says. “There’s really no reason to decline at the rate that most people do.”

He certainly isn’t slowing down. On the contrary, he’s intent on beating his best times.