Where does one draw the line between smart school planning and potential overbuilding? With this question comes a cautionary backstory: In the 1960s, APS enrollment topped 25,000 students as the massive Baby Boomer generation passed through its formative years, but by 1988 the number of students had dipped to below 15,000. At that point, the county had more schools than it needed, so it closed some of them.

Whereas Arlington had 38 elementary schools in 1955, it now has 23.

During the 2015-2016 school year, APS technically operated at full capacity, falling just 175 seats short of accommodating its total student population. But the distribution of students wasn’t even. Some schools were nearly bursting at the seams, while a few others had wiggle room.

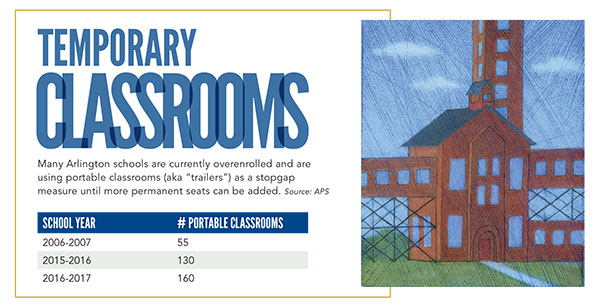

Today, about 1 in 10 Arlington schoolchildren no longer fit inside the brick-and-mortar buildings where they learn. This mismatch has forced many schools to stretch space with relocatable classrooms, which do not count as official permanent “seats.”

School officials report that APS spent $16 million to purchase and lease 160 trailers over the last decade. The use of portable classrooms has allowed Arlington schools to maintain relatively small average classroom sizes—the smallest in the greater Washington, D.C., region—but it’s also put stress on common areas such as cafeterias, gyms and art rooms.

“Trailers have saved Arlington millions, but their overuse is coming at considerable cost,” says Michael Beer, a father of two APS students and co-chair of the Arlington County Civic Federation’s Schools Committee. One of the less obvious ones, he says, is environmental. “[The modular classrooms] take up a lot of green and recreation space. They add more impermeable surfaces for water runoff. Their energy efficiency cannot be great.”

Yet there may be plenty of trailers on the horizon. Even if APS carries out its plan to add as many as 6,600 more permanent seats by the 2025-2026 school year, the gap between students and seats could still widen, according to school projections.

“[The portable classrooms] aren’t temporary,” Beer predicts. “Some will be in place for 20 or 30 years.”

This time, if APS builds more space than it needs, its first move will be to retire trailers, not close schools. As Arlington School Board member Barbara Kanninen puts it: “We can’t overbuild since we’re way behind [on the construction of permanent seats].”

Can’t APS simply accelerate and bolster its plans to add permanent school capacity? That’s easier said than done, according to Noah Simon, a past PTA president at Arlington Science Focus Elementary and Swanson Middle who served on the Arlington School Board from 2012 to 2014. “I don’t know how more construction would be possible from a financial perspective,” he says.

The trouble is that APS will be paying down debt it’s already incurred on school construction projects (plus interest) for the foreseeable future.

Since 2006, APS has spent $572 million on school construction, more than half of it (roughly $300 million) to rebuild Arlington’s three major high schools: Yorktown, Washington-Lee and Wakefield. Unfortunately, those projects ate up public funds without adding any new seats.

“The staff and boards and community advisers reached a consensus 10 to 15 years ago” on the plan to replace the high school buildings without increasing capacity, says Nauck resident Moira Forbes, a mother of two APS students who served on the school system’s Budget Advisory Committee between 2010 and 2016, as well as on the APS Facilities Study Committee in 2015. “This was a collective failure.

“Every time I see the growth projections I just want to curl up in the fetal position,” Forbes says.

Historically, Arlington has relied heavily on bond revenue to pay for school construction. And the fact that the county has maintained a AAA-bond rating (the highest credit rating a municipality can have) has kept borrowing costs to a minimum amid record-low interest rates. In November, Arlingtonians will vote on a referendum calling for $139 million in additional school bonds over the next two years. It is widely expected to pass.

But even with voter support, there are limits to how much money Arlington can raise in this way. To maintain Arlington’s top-notch credit rating, APS has always kept the total of the interest and principal repayments (known as debt service) paid in a given year below 10 percent of its yearly operating budget. It has tiptoed toward that cap for years.

It doesn’t help that Arlington’s surge in school-age kids has coincided with an uptick in commercial office vacancies, which are now hovering around 20 percent countywide (double the historic average). Every percentage point of empty office space cuts tax receipts by $3.4 million, says County Manager Mark Schwartz. Which leaves less money for schools and everything else.

So it’s helpful that APS’s current 10-year construction plan incorporates two subtle funding boosts from the county government.

First, the plan calls for piercing that 10 percent cap on debt service for school construction by 2021, with the county board’s blessing and cooperation. (To safeguard its top-tier status in the bond market, the county would keep debt service on non-school construction below 10 percent of its operating budget.)

Second, the county is handing over the Fenwick Center property (which sits adjacent to the Arlington Career Center and a library branch on Walter Reed Drive) to APS after years of non-school use.

This will allow for an expansion of Arlington Tech, a new countywide high school program focused on project- and work-based learning. Its pilot program kicked off this fall with 40 freshmen.