On May 15, 2010, Amanda Bisnauth-Thomas woke up with a headache. Her right hand, she noticed, was shaking a little. Feeling too ill to drive to her son’s Little League game at Jamestown Elementary, she asked her husband, Michael, to take the wheel. Halfway through the baseball game, Amanda began slurring her words. That’s when Michael drove her to the emergency room at Virginia Hospital Center.

At 41, Amanda had never had a serious health problem in her life. So the couple was floored when the ER doctor returned, lab results in hand, and delivered the startling news that Amanda’s liver was failing. She needed a transplant immediately.

“Okay, I’ll check myself in on Monday,” she said.

“You don’t understand,” the doctor replied. “We’re putting you in an ambulance right now.” The transport sped to MedStar Georgetown University Hospital in Washington, D.C., which specializes in organ transplants.

That’s about the last thing Amanda remembers from that day. Her liver was deteriorating rapidly, and her blood stopped clotting. Michael, a Foreign Service officer (he had met Amanda while he was stationed in her native Guyana), watched as his wife of 14 years lay in a hospital bed, her long, dark hair fanned over a pillow, while blood leaking from her veins turned her skin black and the whites of her eyes bright red.

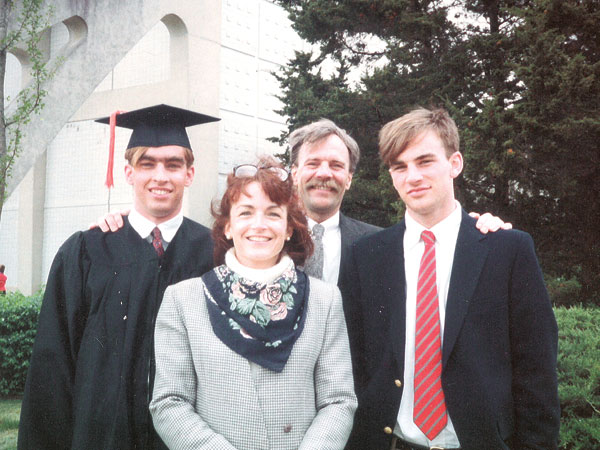

Amanda Bisnauth-Thomas with her husband, Michael, and Arley Interiano, whose son Jami’s organs saved Amanda’s life.

Amanda’s condition was so dire that once she was placed on the organ transplant list, “she immediately went to number one nationwide,” Michael recalls, meaning she was eligible to receive the next liver that became available in the U.S.

Fortunately for her, it arrived on a charter flight from Texas the following day.

During the transplant, surgeons found that the liver Amanda had been born with was completely destroyed, although they couldn’t figure out why. After sending out tissue biopsies and ruling out factors as far-fetched as eating poisonous mushrooms, they still came back with nothing. To this day, the cause “remains the big mystery,” Michael says.

Amanda recovered, and within a few weeks, she was back home in the upstairs bedroom of her family’s brick colonial in Arlington Forest, reading murder mysteries and watching House M.D. while she regained her strength. Sometimes Michael and their son, Thornton, then a second-grader at K.W. Barrett Elementary, piled into the bed with her while she rested.

But the family’s return to normalcy was short-lived. Seven months later, Amanda’s body rejected the new liver—an outcome that occurs in one-quarter to one-half of all liver transplant recipients, according to researchers at the University of California, San Francisco. (Following a transplant, a patient’s body may suddenly recognize the new organ as a foreign object and develop antibodies to attack it. Though most organ recipients are treated with immunosuppressant drugs to prevent this, they don’t always work.)

Plus, there were complications. Amanda developed internal bleeding after a biopsy was performed to investigate why the liver had failed. She was moved into the ICU, where her kidneys started to shut down and her problems snowballed.

Soon, she developed pneumonia and had to be hooked up to a ventilator to help her breathe. Sepsis set in, and she needed round-the-clock kidney dialysis, relying on a machine to filter waste from her bloodstream.

Though she was sedated and no longer conscious, Michael decorated her cramped hospital room—filled with “so many machines, it was like a science fiction movie,” he says—with 8-by-10 enlargements of family photos. Thornton eating spaghetti. Thornton gingerly holding a blue crab on a trip to the Chesapeake Bay. Thornton grinning next to the giant vase of yellow orchids (Amanda’s favorite flower) that Michael had sent her on their anniversary.

“We’re four weeks into this,” Michael recalls, “and the head of the ICU, a really nice guy, says to me, ‘Mr. Thomas, can I talk to you later?’ I called my dad, and I said, ‘Dad, I need you.’ Because I knew what the conversation was going to be.

[The doctor] said, ‘You have to get ready because she’s probably not going to make it.’ ”

But Amanda’s condition improved. Within two weeks, she was able to breathe on her own, and the doctors woke her up from sedation. Her kidneys still weren’t functioning, so she remained hooked up to a dialysis machine. Eventually the medical team determined that she was strong enough to endure a second transplant surgery. This time, though, she needed a new kidney as well as a liver.

IN THE WORLD of transplants, demand is highest for kidneys, those bean-shaped organs whose critical role is to filter waste products, salt and excess fluids from the blood (in the process, they also help to regulate blood pressure, electrolyte balance and red blood cell production). Among the 123,000 Americans who are currently waiting for an organ transplant, more than 100,000 need a new kidney, according to the National Kidney Foundation.

Fewer than one in five of those people will receive one. It takes 3.6 years, on average, to reach the top of the organ recipient list maintained by the United Network for Organ Sharing, a private, nonprofit organization that manages the nation’s organ transplant system under contract with the federal government. Some patients don’t survive that long on dialysis. Others become too sick to receive a transplant.

Amanda had one circumstance in her favor. Patients who need multiple organs fall into a special category that places them farther up in line. Which explains how she came to receive both a liver and a kidney on March 5, 2011, by way of Inova Fairfax Hospital in Falls Church just one day after she was placed back on the waiting list for organs recovered from deceased donors. After 12 hours of surgery and two more weeks in a hospital bed, she was well enough to go home.

Three months later, Amanda learned the identity of the donor who had given her a third chance at life: Jami Angel Interiano, a 19-year-old from Woodbridge, who had died from a gunshot wound to the head. His family wanted to meet her.

A short time later, she found herself walking into a packed conference room at the Washington Regional Transplant Consortium in Annandale to find more than 20 of Jami’s relatives waiting. She wasn’t the only newcomer in the room. There were three others who also came to meet Jami’s family that day: Chuck Campbell, a car salesman from Delaware who had received Jami’s lungs; George Ortega, a limo driver from Florida who had received his heart; and Kelly Coles, a nurse from Upper Marlboro, Maryland, who had received his other kidney. Together, they heard stories about the teenager who had saved their lives, a devoted Dallas Cowboys fan who loved ’80s music.

On Oct. 1, the whole group met up again to celebrate Jami’s birthday. The annual birthday party has been a group tradition ever since.

NOT ALL KIDNEY transplants come from donors who have died. Ever since 1954, when the first kidney was successfully transplanted from a living donor, certain patients have been able to circumvent the organ waiting list by finding a friend, relative or kindhearted stranger who is willing to part with one. Humans, like other animals, are born with two kidneys, but a healthy person can function normally with just one.

Paul Fuss. Photo by Sean Scheidt.

While Amanda lay in a hospital bed, awaiting her second transplant surgery, Paul Fuss was living a busy life a few miles away in Arlington’s Claremont neighborhood—thanks to the kidney he had received from his father 19 years earlier.

A mechanical engineer by training, the trim 6-footer was spending his days analyzing fire investigations for the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, returning home each night to the brick rambler he shares with his wife, J.J. Gardiner, a teacher at Arlington Unitarian Cooperative Preschool, and their two sons.

When he was 5 years old, Paul was diagnosed with Alport Syndrome, a genetic condition that occurs in roughly 1 out of 50,000 newborns, according to the National Institutes of Health, and can cause hearing loss, vision problems and kidney failure. He almost made it through college at Virginia Tech before his kidneys stopped working.

Fortunately, when that time came, his father, Steve, was a match. Both had the same blood type, and tissue testing found that Steve matched three of Paul’s six main antigens (proteins found in cells), meaning that Paul’s immune system was likely to accept his dad’s kidney. In 1992, over Christmas break during Paul’s senior year, Steve gave his son the unique holiday gift of a working kidney.

It lasted for 22 years. But in early 2014, Paul learned that the transplanted organ was beginning to fail. He lost his appetite, dropped weight and began retaining fluid, which caused his feet and ankles to swell. By September, his kidney function was poor enough to warrant placement on the national transplant waiting list. He was 44.

Paul Fuss with his wife, J.J., in April.

Though his condition was life-threatening, Paul wasn’t too worried. Preliminary tests years earlier had suggested that his mother, Christine, was also a likely match for his blood and tissue types. “She always said, ‘Whenever you need one, you’ve got mine,’ ” he remembers. “I thought it would be easy.”

It turned out not to be. Paul was shocked when, early in the screening process, doctors at Georgetown Hospital ruled out his mom as a donor.

Others stepped up and offered Paul their kidneys. Before long, nearly 20 people had entered the screening process, including Paul’s wife, J.J.; her sister, Angie O’Reilly; an uncle; and several family friends.

“I was blown away,” Paul says. “I thought, All I need is one [match].”

What he didn’t realize is that it’s usually much harder to find a matching kidney the second time around. In addition to his immune system’s original antibodies, Paul was now hosting an entire second set of antibodies that his body had produced in response to his father’s kidney.

The fall of 2014 slipped away as volunteers whose blood and tissue types proved compatible with Paul’s graduated to more complex tests—including MRI scans and X-rays, along with mental health screenings to determine whether they were psychologically prepared to donate a kidney.

J.J. remembers the devastating news that came during a visit to Angie’s home in Manhattan over Thanksgiving weekend. “We were out at a restaurant, and I got the call that said I was not compatible with [Paul]. And we walked back to Angie’s apartment, and her phone rang … and she was not compatible.”

In the end, every person who had offered to donate a kidney to Paul was not a match. “It was awful,” J.J. says. “It just felt like, That’s not possible, there are too many of us.”

STILL, THE FAMILY had one last hope. In the decades after Paul’s first transplant, hospitals had begun experimenting with a different means of matching patients with kidneys, called a paired exchange. And thanks to advances in database technology, this option was gaining momentum.

Paul Fuss with his family at his college graduation in 1993.

The idea behind paired exchanges is simple. Although J.J. couldn’t give Paul a kidney, she might be an excellent match for someone else who needed one. If that person had a donor who matched Paul, the two pairs could basically swap kidneys. But in order for this to work, both donors had to match each other’s recipients.

The key to arranging such exchanges is software that can compare hundreds of patients and dozens of clinical variables at a time—and a pool of people large enough for most pairs to find a match. Georgetown Hospital referred Paul to the National Kidney Registry, a nonprofit based in Long Island, New York, and the largest, by far, of three nationwide kidney exchange programs.

Through the kidney registry, Paul’s blood type, combined with medical data on more than a dozen of his antigens and conflicting antibodies, was entered into a database that tracks the 250 people who are seeking a kidney on any given day, along with some 300 potential donors. Upon receiving new information, the database uses an algorithm to search for the best possible pairs.

Matching kidneys, it turns out, requires a great deal of computing power. When the National Kidney Registry was launched in 2008, it took up to 12 hours for the registry’s file servers to look for matches every time a new donor or recipient was added to the pool.

Now, thanks to custom-built, “liquid-cooled machines with the fastest processors you can buy,” the data can be crunched in as little as 30 minutes, according to Joe Sinacore, the registry’s director of education and development.

The computers run different scenarios continuously, and on average, recipients in the registry wait 70 days for a suitable pairing—although people like Paul Fuss, who are hard to match because of a previous transplant, can sometimes wait much longer.

The present-day software can also do something more complicated than previous matching programs. While pairs whose profiles align can still trade kidneys, the registry is sometimes approached by what organizers call a “good Samaritan” donor—a person who is willing to donate a kidney to anyone in need, without the stipulation of needing one for a designated recipient in return. The good Samaritan changes the math, making it possible to link together a long daisy chain of donors and recipients, all arranged to create the best possible match for each person.

As a result, chains can help find kidneys for patients who are very hard to match. The last recipient in the chain becomes someone on the transplant waiting list who doesn’t have a donor standing by.

BY MID-JANUARY 2015, Paul was shrouded in a constant fog of fatigue. Although he continued to work, he could do little else and spent most of his spare time sleeping, his face puffy from the excess fluids his kidneys were unable to filter out of his bloodstream. Soon, his kidney function was so poor that he needed to arrange for dialysis.

Meanwhile, his sister-in-law Angie became the first of his many volunteers to pass all the tests required to become a kidney donor. Though she wasn’t a match for Paul, Georgetown Hospital forwarded her data to the National Kidney Registry with hopes of engineering a paired exchange.

“We all just braced ourselves for a long wait,” says Angie, who had quit her human resources job at an investment bank to stay home with her kids. “Months, if not years, of waiting.”

Two hours after Angie’s information hit the database, the system found a match. “I was absolutely ecstatic,” she remembers. “It was like being told you just won the lottery.”

Paul was in his nephrologist’s office discussing dialysis options when his cellphone rang. “I looked at it,” he says, “and I recognized it as a hospital exchange. I said, ‘You mind if I take this?’ ” The news ended their discussion. His transplant was already scheduled for Feb. 18.

A short time later, Paul and J.J. were told that Paul’s transplant would be part of a chain of seven kidney transplants. His kidney would come from New York, and Angie’s would be flown to California. But there was one aspect of the donation chain that seemed tenuous. If only one link in the chain were to be broken—if one donor or recipient became ill, for example, or changed their mind—the whole arrangement would collapse. “I tried really hard, leading up to it, not to think about that,” J.J. says.

The chain proceeded smoothly right up until the night before Paul’s surgery, when a snowstorm struck the East Coast. The next morning, J.J. looked out the window at a blanket of white only to see a group of neighbors walking down their street near Barcroft Park, armed with shovels. They were determined to get Paul to Georgetown Hospital on time.

As he was being prepped for surgery, Paul learned that his donation chain had expanded from seven transplants to more than 30.

There was just one hitch: He had managed to reach the hospital on schedule, but his new kidney, which was headed south on I-95 from New York, wasn’t there yet. Its journey had been slowed down by the blizzard.

“They had a GPS on the courier truck,” he says. “I remember being in pre-op and hearing, ‘[The kidney] is making good progress, it’s in Philadelphia now … when it gets to Baltimore, we’re going to take you back.’ ”

It arrived safely, and by the end of the day, it was already at work inside Paul’s body.

TODAY, PAUL SAYS his life has mostly returned to normal, with some adjustments. He uses a smartphone app to track the four liters of water he must drink every day to keep his new kidney hydrated. And he’s careful to steer clear of foods that pose a higher risk of harboring bacteria—such as buffets and undercooked meats—understanding that the immunosuppressant drugs that he takes daily to keep his body from rejecting the new kidney also leave him susceptible to infections.

He recently spent two days in the hospital with gout (a common complication for people with kidney transplants) and is diligent about slathering on SPF-50 sunscreen, given that kidney patients run an elevated risk of developing skin cancer.

Otherwise, he says, he’s back to feasting on blueberry pancakes at Bob & Edith’s Diner, heading out for family camping trips in the Shenandoah and practicing baseball with his two sons, a seventh-grader at Kenmore Middle School and a fourth-grader at Campbell Elementary. “I try not to let [kidney disease] dictate the way I live my life,” he says.

Paul’s chain, known as Chain 357, still holds the record as the longest donation chain to date, having linked 35 kidney transplants in 25 different U.S. hospitals, according to Sinacore. It started when 48-year-old attorney Kathy Hart of Minneapolis approached the National Kidney Registry and volunteered to become a good Samaritan donor by giving her kidney to anyone who needed it.

What prompts a complete stranger to engage in such an utterly invasive and selfless act of kindness? Sinacore says that good Samaritans often start out offering to donate a kidney to a friend or family member and end up not being needed in that particular scenario, but are awestruck by the transformation they then witness.

“They are usually pretty moved by the miracle of transplantation that finally took place for their loved one,” he explains. “If you see [transplant patients] the day before surgery, they look like hell. They look horrible. The one thing that motivates people … is to see how literally, in the weeks after that transplant, they look like a new human being.”

AMANDA Bisnauth-Thomas says she hears that a lot. “The first response I get when people meet me is that I don’t look like someone who’s had several transplants.”

She doesn’t. Looking back, there’s something surreal about the time when members of the Barrett Elementary PTA rallied during the darkest days of her illness, delivering family meals to Michael and Thornton for three months straight. Now Amanda is usually the one in the kitchen, inviting friends and neighbors to sample the dishes she’s cooked up with the eggplant, okra and Scotch bonnet peppers that she grows in her garden. Her hot sauce “makes even West Africans cry,” says Michael, who now enjoys long walks with his wife in Arlington’s Lubber Run Park.

Amanda still maintains close ties with the family whose young son’s organs saved her life—so close, she says jokingly, “that I am expected to take sides in family arguments.” Sometimes she and Thornton—now a sixth-grader at Kenmore Middle School—go fishing with Jami’s father, José Interiano, at his favorite fishing hole in Woodbridge.

The transplant experience has also solidified her bond with Kelly Coles, the woman who received Jami’s other kidney. Referring to themselves as “the kidney sisters,” they like to go shopping together and recently splurged on tickets to see Cirque de Soleil. “I feel like I have to catch up on all the moments that I missed with my friends and family,” Amanda says.

But she’s also intent on paying it forward. Before, “I was never one to talk about myself,” she says. Now, as a tireless advocate for organ donation, she is accustomed to telling her story at community health fairs, schools and other public venues. One person’s organs can save eight lives, she stresses. “So if I spend two hours and I get one person to sign up [to become an organ donor], that’s eight lives,” she says. “That’s the way I look at it.”

Living with transplanted organs can be a job in itself. Like Paul, Amanda takes drugs that suppress her immune system in order to prevent her body from attacking her new liver and kidney. “You’re warned from day one that you have to take all these meds,” she says, “and one of the side effects is that you can get an infection at any time.” In the past year, a stomach infection and other complications kept her in the hospital for 45 days.

Still, she keeps things in perspective. “I can’t complain if I get 320 days [per year] that I don’t have to be in the hospital,” she says. “That’s a good deal to me.”

TRANSPLANTS CAN also be life-changing for live donors who offer the gift of a kidney. Angie O’Reilly still remembers waking up in the recovery room at Georgetown Hospital after donating one of her kidneys on behalf of her brother-in-law Paul. Her surgeon stopped by to tell her about the woman who had received her kidney as part of Chain 357.

“The surgeon starting telling me how long [this patient] had been waiting and that she was doing really well,” Angie says. In fact, the woman had been waiting for 34 months. She had formed antibodies against so many tissue types that she was considered almost impossible to match.

Upon hearing this, Angie was reminded of the words she’d heard from a transplant coordinator months earlier, during a particularly low moment when she’d been feeling hopeless. “You could be someone’s needle in a haystack,” the transplant coordinator had told her.

“I’m heavily medicated and very emotional,” Angie says, “and I’m lying there [in the recovery unit] sobbing. Up to that point, I had always thought, I don’t care who gets my kidney as long as Paul gets one. But in that moment … that’s when it hit me. This really is something incredible, that all of these unrelated people, complete strangers, can help each other get to a much better place.”

Laurie McClellan lives in Arlington and writes about science, nature and health. See more of her work at www.lauriemcclellan.com.