I had already experienced natural West Virginia—hiking and cross-country skiing its state and national parks, birdwatching in its national wildlife refuges and white-water-rafting its rivers. And I’d already done artsy-foodie-spa West Virginia, with its high-end art galleries, chichi coffee shops and mineral springs.

But I had never really explored the historic past of a state where turn-of-the-century immigrant families from Italy, Hungary, Poland and Switzerland were once lured by plentiful hard work. I had never plunked myself down in the epicenter of its most valuable homegrown resources—coal and timber, which built the infrastructure of our nation—where companies once bought and logged wildernesses so vast that they could never imagine running out of trees.

Craving a different kind of experience, my husband, Neil, and I embarked on a journey through the West Virginia that once was—the prosperous and the terrible—where steep mountain passes and subterranean mines still bear witness to a hardscrabble existence.

We returned from our road trip with a new appreciation for the only state that exists solely within the Appalachians, the only state to secede from another state during the Civil War, and a state that’s as proud as it ever was of the long road it has traveled. These are the historic spots we visited.

Beckley Exhibition Coal Mine

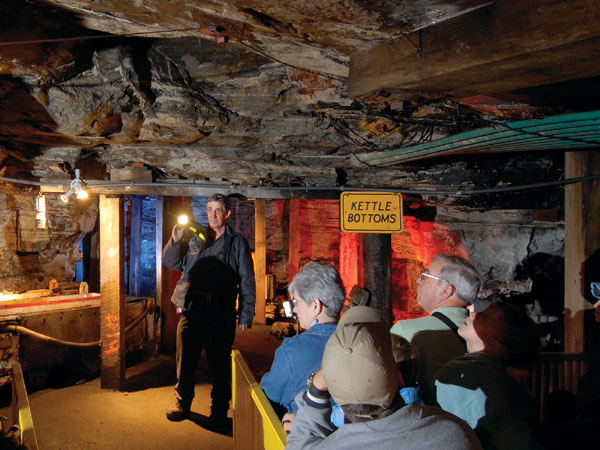

After spending 25 minutes underground on an open-air “mantrip” (trolley) in the dark and narrow passageway of the Beckley Exhibition Coal Mine, I am really glad to see sunlight. We’ve just learned how men risked their lives blasting coal out of the earth, chopping the resource out of seams for less money than they could live on. And we now know the difference between “blackdamp” (an asphyxiant that can kill you by sucking the air right out of you) and “firedamp” (a flammable, explosive gas).

Our tour leader, a former miner, gives us the lowdown on what it was like to spend daylight hours underground, paid not by the hour, but rather only for each 1-ton cart resulting from the day’s work. (That is, provided someone didn’t cheat and attach his name to your cart and take credit for it.)

Aboveground, a walk through the re-created 1900s-era mining town—composed of authentic but plain, whitewashed and weatherboarded buildings—shows the different classes and how people lived.

Comparing the “bachelor’s shanty” (which is no larger than my galley kitchen) with the standard coal company house for families, and the “super’s house” (a downright mansion), it’s no wonder a miner who worked his way up to superintendent was hated so much by his men.

Our guide, a coal-miner’s daughter, explains that by the time a man reached that level, the mine usually transferred him to another mine where he didn’t know anyone. There, he could be as strict and unfair as he wanted to be, thus assuring his good standing with the company, as none of his subordinates were his friends.

The Pemberton Coal Camp Church and Helen Coal Camp School offer more glimpses of what day-to-day life was like back then (with schoolbooks and lessons from that era), while the Exhibition Coal Mine Museum shows off its collection of miners’ lamps, tools, equipment and clothing. A handout lists the hundreds of products we still use today that stem, in some way, from coal—including paint thinner, clothing dyes, electrical insulation and baking powder.

Cass Scenic Railroad State Park

Black smoke belches out of the locomotive smokestack as the “fire man” manually shovels 4.5 tons of coal—that’s six shovels-full every 30 seconds for four hours—into the firebox. The coal heats up 7,000 gallons of water until it boils so that the steam can power the train. This is the way it was done in 1901, when immigrant workers laid these tracks and the same Shay locomotives carried logs down the mountain to the mill in Cass, and this is the way it’s still done today in the nation’s only surviving lumber company town, which the state purchased and made into a park, starting in 1961.

As the train wends its way up 11 miles to Bald Knob, a retired railroad man teaches us about the history of logging and railroads in West Virginia. Our first stop is Whittaker Station, the site of a Hungarian railroad laborers’ camp in 1900 and a place where visitors can now view a re-created 1940s logging camp. We then chug our way up to the panoramic view at Bald Knob, the third-highest point in the state, at 4,700 feet. (An alternate train route goes to Old Spruce, a 1902 ghost town once known as the “highest and coldest town east of the Mississippi.”)

The ride is noisy, sooty and cold (even in August)—and unforgettable, even for non-train-buffs. Not only does the train manage several steep hairpin switchbacks, but it sustains an 11-percent-grade ascent. (For a comparison, the maximum grade allowed on U.S. highways is 7 percent.) Visitors with reservations can get off at various points to spend the night in converted cabooses.

Back at the depot, Neil and I grab a quick bite at The Last Run Restaurant—a no-frills burger-and-grilled-cheese kind of place located in the 1902 Cass Company Store—before heading out to self-tour the restored company town of Cass. It’s an unpopulated enclave of simple, two-story, white logging company houses (now open and available for vacation rentals) connected by wooden walkways, along with a hotel, a Masonic lodge, a church and a jail.

Seneca State Forest “Pioneer Cabins”

It’s a bit nerve-racking to have to light a match every time you want to turn a light on, but the propane lights count among the luxury amenities at Seneca State Forest’s “pioneer cabins.” In addition, our cabin offers a kitchen with a propane refrigerator, a fireplace, a woodstove, a fully stocked woodshed and a screened-in porch overlooking a lake.

The cabins don’t have running water or flushing toilets, but Neil and I consider this a small price to pay for the experience of going back in time. (There are coin-operated showers and real bathrooms at the visitors’ center a couple miles away for those who aren’t so crazy about roughing it.)

Built for recreation by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) between 1934 and 1938, eight rustic cabins line the similarly CCC-engineered Seneca Lake. At four acres, it’s a small pond, really, where we take out a canoe and paddle in the setting sun on our first evening. Then we pump water from the well near the cabin, pull out our propane stove, make a quick dinner on the porch—beans and rice with dehydrated veggies—and do the things it seems we only do when we’re “away from it all”: read, talk, play games.

Later, snuggling under colorful quilts and wool Army blankets, we sleep the kind of sleep you only get when surrounded by fresh mountain air. The cabins are a perfect place to base yourself before and after a trip to Cass (17 miles away), or when partaking in surrounding attractions. The park offers 23 miles of trails for hiking and biking, as well as 10 campsites.

Helvetia

While many residents of West Virginia can probably trace their history back to some European ancestor who came over to find work mining, timbering or building railroads in the 1800s, those who live in Helvetia are still living the life, descended from the Swiss who settled the village in 1869. Having spent a summer in Switzerland in my teens, I have a particular interest in exploring this odd little Swiss outpost.

The road to Helvetia (pronounced hell-vay-sha), population 25, is narrow, winding and precipitous. We spend at least an hour behind an overloaded coal truck (which is listing to one side and going well beyond the speed limit) as drivers coming from the opposite direction zoom past at breakneck speed, as if they are being paid by the load. One turns off into a mine, another at a railroad, while we continue through the steep mountains with second- or third-growth forest at every view. We also pass the occasional run-down house, trailer or bar—desolate properties that are seemingly on the edge.

Then, finally, like a black-and-white movie morphing into Technicolor, we come to a low, lush, green valley with a river running through it, and a town brightened with flower boxes of reds and pinks and oranges; a baby-blue house; a yellow painted store; and decorative Germanic stencil art at every turn.

The moniker, Helvetia, comes from the Latin name for Switzerland, Confederatio Helvetica—or the Swiss Confederation. In the Helvetia Village Historic District, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, visitors can find a church, an inn, a post office, a community hall, a cultural museum and other buildings. Our destination for the day is the Hutte Swiss Restaurant, located at “the intersection” (there’s only one).

Upon arrival, I almost expect our waitress—who is wearing early 1900s period farm wife attire—to speak in the Swiss-German accent I remember from my travels. But her voice imparts instead a native West Virginia twang, with all its colorful extra letters and syllables, setting off a cross-cultural explosion in my head. We happily feast on Helvetia cheese; bratwurst; the best sauerkraut I’ve ever experienced (sweet and tangy); hot applesauce; a potato pancake not unlike Jewish latkes; homemade split-pea soup that’s to die for; and peach cobbler with a unique Marshmallow-Fluff-like topping.

Down the road, we purchase two Helvetia Shepherds wool scarves at the Helvetia General Store, made from sheep raised and sheared in this very valley. We then visit the historic cemetery, where some grave markers are carved in German. We vow to return to this pretty little hamlet and, next time, stay the night.

Arthurdale

Also known as “Eleanor’s Little Village,” Arthurdale was FDR’s first New Deal homestead community and is an essential part of any West Virginia historic road trip. At its genesis, Mrs. Roosevelt was moved by the plight of company-town families who were deeply in debt to their employers for their houses and provisions. Many were compelled to borrow “scrip” (substitute legal tender, redeemable only at company stores) at high interest rates, which they could never repay.

During the Great Depression, when many such families were unable to feed their children, the government purchased land from a man named Richard Arthur, built 165 homestead houses and selected residents based on applications with strict criteria. Arthurdale—now a National Historic District—was Eleanor’s pet project, created with the hope of returning families to self-sufficiency.

Families residing in Arthurdale were responsible for their own rent and expenses, but they worked in the cooperative industries and businesses that were started there. Men forged iron, built furniture, worked at the automotive service station and farmed, while women were involved in spinning and weaving, making clothing, rugs, aprons and tablecloths to sell.

Arthurdale Heritage, a nonprofit organization dedicated to the preservation of this experimental community, provides us with our own private tour, including stops at the New Deal Homestead Museum, a forge, a service station, a dance hall (where one young Arthurdale resident reportedly got to dance the Virginia Reel with Eleanor herself) and one of the original homes.

Afterward, we take a self-guided driving tour through the town, which is still inhabited today (as privately owned homes), playing “I spy” to locate the three house types that were constructed between 1933 and 1937 in this charming, but ultimately failed, attempt at a more equitable distribution of wealth.

More Tour Stops

Got extra time? Consider adding these stops to your road trip itinerary.

Thomas

Located just three miles from the headwaters of the Potomac River, Thomas was once a coal company town. Much of its history is preserved in the 48 properties in the City of Thomas Commercial Historic District, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. You can pick up a copy of the walking tour map from any number of businesses in Thomas, or download it here. It’s a 0.7-mile, 45-minute leisurely walk.

Thurmond

One of West Virginia’s 69 ghost towns, Thurmond—once a boomtown in the coal and railroad heyday—is now preserved and managed by the National Park Service as part of the New River Gorge National River.

Arlingtonian Sue Eisenfeld writes about history, travel and nature. She is the author of Shenandoah: A Story of Conservation and Betrayal (University of Nebraska Press, 2015). Find her at www.sueeisenfeld.com