1. View a Tattoo

Not the ink kind; the military kind. The term tattoo, which dates back more than 300 years, refers to a bugle call at day’s end to signal soldiers that it was time to sleep. It’s one of the many sounds you’ll hear during the Twilight Tattoo at Fort Myer’s Summerall Field, an hourlong spectacle that blends more than two centuries of U.S. military history and pageantry with dashes of rock ’n’ roll and poignancy.

The show, which is held most Wednesday nights through Aug. 3 (no performances July 6 and 13), features the Army’s “Pershing’s Own” band and other Army musicians performing tunes ranging from “The Star-Spangled Banner” to the World

War I battle cry “Over There” and Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America.”

For the cast members, this patriotic display isn’t just an act. The auditions “are very competitive,” says 1st Lt. Marcus Jeffries, 33, of North Chicago, who is resplendent in a deep-blue wool uniform patterned after those worn during the Revolutionary War. With a tricorn hat on his head and spontoon (a short pike) in hand, he’s just completed a dress rehearsal along with 200 fellow active-duty soldiers in the 3rd U.S. Infantry Regiment, the oldest in the nation.

“I would have loved to have attended something like this” as a high-school student back in Erie, Pennsylvania, says Sgt. Justin Cullmer, 26, who has a role in the Korean War segment. “A lot of this history I didn’t know when I got here.”

Sgt. 1st Class Heather Tribble, 35, of Kansas City, Kansas, demonstrates on her fife a certain call that would have let soldiers know that danger was nigh. The Old Guard Fife and Drum Corps, of which she is a member, is the only unit of its kind in the entire U.S. military. “When we’re all playing this, you can hear it for miles.”

—Amy Rogers Nazarov

2. Play in a Fort

“All quiet along the Potomac tonight,” began a famous Civil War song, “except now and then a stray picket … is shot, as he walks on his beat to and fro … by a rifleman hid in the thicket.”

Being picked off was a natural fear for soldiers stationed at Fort C.F. Smith, one of dozens of Union-occupied forts and batteries that circled Washington during the Civil War. While only one true battle occurred at any of those fortifications (Fort Stevens in D.C.), soldiers constantly prepared for a surprise attack on the Union capital.

Built in 1863, Fort C.F. Smith was named for a Union commander who had served with Ulysses S. Grant and died the previous year. According to official military records, the encampment was considered a well-built “first class” fort among the “Arlington line” of defenses along the Potomac River, which included Fort Ethan Allen (located in what is present-day Arlington), Fort Marcy in McLean, and Fort Ward in Alexandria.

Fort C.F. Smith is now one of the best-preserved (and few remaining) Civil War forts in Northern Virginia, and it may be the best hidden. Tucked away on a residential street in Arlington’s Woodmont neighborhood near Spout Run, the 19-acre, county-owned park contains visible earthworks; remnants of a bombproof (a shelter built to withstand artillery fire); 11 of the fort’s original 22 gun emplacements and a half mile of woodland trails. It’s also home to Arlington’s largest tree—a tulip poplar measuring 21 feet in circumference that likely predates the Civil War.

The property’s historic Hendry House, built in the early 20th century, is named for the previous owner, Ernest Hendry, a gastroenterologist and amateur botanist whose green thumb is still evident in preserved ornamental plantings such as gingkos and Japanese raisin trees.

Today their greenery forms a lovely backdrop for weddings (Hendry House can be reserved for events), picnics and leisurely strolls.

—Kim O’Connell

3. Picture This

Come for the Tiffany stained-glass windows. Stay for the inspiring and sometimes playful watercolors, oil canvases and other works at the Arlington Arts Center. The ornate windows in AAC’s Tiffany Gallery—whose jewel tones shine even on an overcast day—were salvaged from Arlington’s Abbey Mausoleum, a palatial crypt built in 1924 just south of Arlington National Cemetery that spanned more than 50,000 square feet and housed hundreds of remains until it was torn down in 2001. (The demolition was temporarily suspended when a worker noticed Louis Comfort Tiffany’s signature on one of the original 13 panels.)

But the windows aren’t all there is to see at this mecca for art lovers on Wilson Boulevard in Virginia Square. AAC maintains nine galleries and rotating exhibits inside the historic Maury School, built in 1910.

Working artists in residence occupy a dozen studios on the building’s top floor, most of which are leased for two-year stints. AAC also offers art classes and summer art camps for kids, and its wide lawn is a prime spot for sculptural installations by local artists.

“I often get off my bike to take a look,” says Henry Dunbar, director of BikeArlington, who passes by routinely. He says he was particularly drawn to sculptor Foon Sham’s “Chapel Oak Vessel”—an organic structure made from pieces of a tree struck by lightning, which graced the lawn a couple of years back.

—Amy Rogers Nazarov

4. Find Your Spirit

You never know what you might discover at Botanica Boricua, an authentic Latino botánica (directly translated as “botany”) specializing in medicinal herbs, religious statuaries, amulets and other mystical products, at 2634 Columbia Pike.

Inside this unassuming storefront on the Pike is a visual feast. Big-bellied Buddhas sit shoulder to shoulder with archangels, their wings unfurled. Hooded, skull-faced figurines of Death brandishing scythes face off against mermaids with graceful tails. Dozens of incense fragrances are stacked in neat piles, while dolls of every skin tone keep watch over customers as they roam the aisles.

“[The store’s] wares are intriguing, both visually and culturally,” says Lloyd Wolf, an Arlington-based photographer. He’s one of the principal organizers of “Living Diversity: The Columbia Pike Documentary Project,” a photo exhibit and book celebrating the people and places of the Pike.

“Our team endeavored to cover as much of the diverse life of the Pike as we could,” Wolf says, “including many of the small businesses.” Botanica Boricua, which shares a block with an Ethiopian grocery, a Bolivian/Korean-owned custom tailor and a Slavic pool and lifeguard business, typifies “the international flavor of the community.” Columbia Pike is, in fact, home to more than 130 ethnic groups.

–Amy Rogers Nazarov

5. See Sparks Fly

Wander the woods off North Military Road on a Friday night and you may happen upon a couple of blacksmiths hammering out ax blades and wrought-iron candlesticks—just like they did in 19th-century Arlington. The Gulf Branch Nature Center Blacksmith Shed, manned by the Blacksmiths’ Guild of the Potomac, is a functioning forge.

The shed’s wooden enclosure, built in 1981 and 1982, is made of timbers from a downed Falls Church tree that was carted over by inmates on work release, explains one volunteer “smithy.”

Gulf Branch Nature Center is also home to Walker Cabin, the partially reassembled homestead originally owned by Robert Walker (1840-1908), whose family gave the land for nearby Walker Chapel on Glebe Road. (Robert was the overseer of the Easter Spring Farm, which was located further up Glebe and owned by the wealthier Henry Lockwood.)

Built in 1871, Walker’s original 32-by-8-foot log cabin survived until the 1970s on the property owned by his descendant Maggie Gutshall. When her land was acquired by Arlington County to create a recreation center and tennis court, the cabin’s remnants were relocated and reassembled a short distance away. The rebuilt structure includes a 19th-century kitchen, parlor and sleeping quarters. The ground floor is stocked with canned goods, Delftware, a mortar and pestle, a rocking chair and a kerosene lamp—evoking the days when Arlington held more farms than suburban homes.

–Charlie Clark

6. Be Morbidly Curious

Arlington National Cemetery may get all the glory, but it’s far from the only historic cemetery in Northern Virginia. In fact, burials at Oakwood Cemetery (www.oakwoodcemetery.co) in Falls Church date back much farther than those at Arlington, to the time of the American Revolution. The first known burial on the site is thought to have occurred in 1779 on the grounds of the former Fairfax Chapel, an old Methodist meetinghouse that was rebuilt in the 19th century and subsequently destroyed by Union soldiers during the Civil War.

The cemetery is located not far from the bustle of Seven Corners but is a world apart from it—a peaceful site full of flowering dogwoods, shady oaks and widely spaced tombstones of all shapes and sizes. Among its more notable interments is Edmund Flagg, who died in November 1890 at the age of 75. Flagg was a fairly well-known novelist and poet of his time who penned several sequels to Alexandre Dumas’ The Count of Monte Cristo, among other works. (Under a gray stone obelisk, Flagg’s memorial reads simply, “A Just Man.”)

Oakwood is also the permanent resting place of Civil War veteran Horace Tuttle, who worked as an astronomer at the Naval Observatory. He was partially responsible for the discovery of Comet Tempel-Tuttle, which orbits every 33 years and is the source of the Leonid meteor shower. Despite his achievement, Tuttle is buried in an unmarked grave.

The 20th century brought activities of a very different kind to this hallowed territory. During World War II, the City of Falls Church erected a fully staffed aircraft observation post, taking advantage of the cemetery’s relative high ground. In the 1990s, the cemetery witnessed a series of eerie cult rituals. The discovery of animal sacrifices and rubber-doll parts flummoxed law enforcement until the cultists eventually moved on. Their motives remain a mystery.

–Kim O’Connell

7. Dig for Secrets

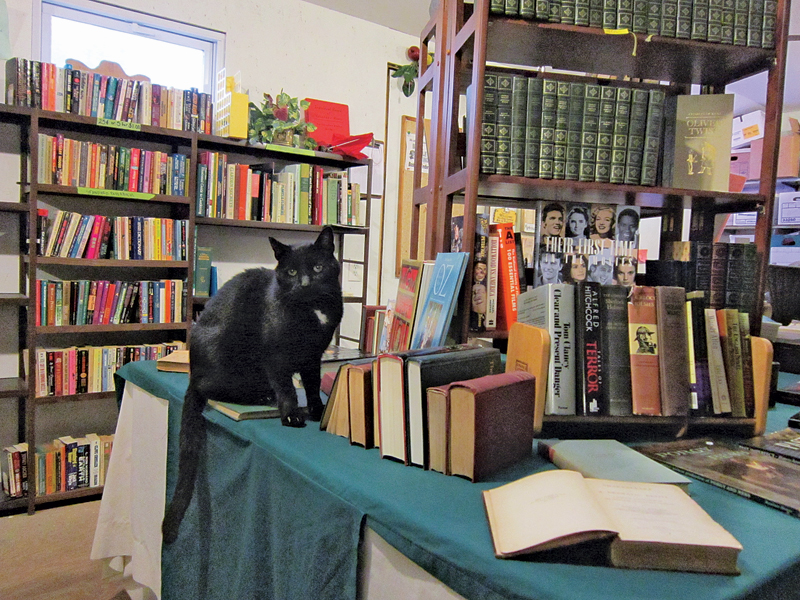

Love rare books and spy swag? The road to this hidden trove twists past barbed-wire fences and checkpoints, plus the occasional warning against entering government property. You’ll think you’re headed someplace you shouldn’t be until a small, gray building comes into view with a simple red sign that reads “BookShop.”

Like the neighboring CIA headquarters, there’s a clandestine quality to BookShop, Used & Rare at Claude Moore Colonial Farm in McLean. Run entirely on donations, this paradise for history buffs carries goods that reflect its proximity to the secretive government agency.

McLean is a factory town of sorts, says BookShop manager Phillip Hanson: “It just so happens that our factory is intelligence and government.” When asked what types of books he receives most often and who supplies them, Hanson offers a response that is coyly tongue-in-cheek: “I would like to name names, but, as you know where we are, I cannot confirm or deny.”

That said, there’s plenty to unearth here—be it an old USSR lapel pin or a century-old copy of Teddy Roosevelt’s The Rough Riders. Dedicated treasure hunters stop in to search high and low for hard-to-find defense and intelligence artifacts, Hanson says. Two recent donations included a book autographed by former CIA director Stansfield Turner and a first edition of Bram Stoker’s biography of the English actor Henry Irving.

Given that the shop is a nonprofit operation—its proceeds fund the educational programs at Claude Moore, a living-history museum showcasing pre-Revolutionary War farm life—BookShop’s inventory is affordable by collectors’ standards.

But there are some things you just can’t put a price tag on, Hanson says: “There’s that experience of finding something that you didn’t know you couldn’t live life without.”

–Matt Blitz

8. Consider Contraband

Vintage opium canisters, glass-encased hash pipes and ads with chubby-cheeked tots shilling “Cocaine Toothache Drops” aren’t your typical museum fare. But the Drug Enforcement Administration Museum & Visitors Center (deamuseum.org) isn’t your typical museum. And yet it’s filled with teachable moments.

The museum’s odd displays—which include 1970s narc attire, a mock headshop and a shrouded mannequin on a gurney—take visitors on a weird and fascinating tour of the global drug trade and the U.S. war on drugs. (Some exhibits will strike the viewer as heartbreakingly timely in light of the nation’s heroin epidemic and recent celebrity deaths linked to prescription-opiate overdoses.)

“Our goal is to present an unbiased view about the dangers of drugs,” says Catie Drew, a fourth-generation Arlingtonian and director of education at the museum, which is housed on the first floor of the DEA headquarters building on Army-Navy Drive in Pentagon City. Open Tuesday-Friday from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. (closed on weekends and holidays), it’s a frequent field trip destination for students in fifth grade and higher—its primary target audience.

Coloring books and junior DEA agent “badges” are available for younger visitors, and the gift shop (yes, there’s a gift shop) sells everything from baby onesies to toy-handcuff keychains, though parents may want to want to steer their kids away from the image of Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar’s blood-soaked body after he was killed in 1993.

Equally sobering are the takeaways from exhibits on the physiological effects of certain drugs. It’s one thing to warn young people, “ ‘Don’t do drugs! They’re bad for you!’ ” Drew says. “I’m a scientist, so I like to show them with science how drugs harm the brain.”

–Amy Rogers Nazarov

9. Get Lost

There aren’t many places in Northern Virginia that make you wonder, If I were to be dropped from the sky in this spot, would I have any idea where I was?

The Potomac Heritage Trail (www.nps.gov/pohe) is one of those places.

Technically known as the Potomac Heritage National Scenic Trail, it is one of only 11 officially designated National Scenic Trails in the nation. And like the more famous Appalachian Trail and Pacific Crest Trail, it’s long—a network of planned and existing trails stretching 830 miles from Pittsburgh and the Ohio River Basin to the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay.

Locally, the 10-mile section that extends from Scott’s Run to Roosevelt Island takes hikers through McLean and Arlington, with nearly constant views of the Potomac River. In early spring, a mind-blowingly beautiful field of Virginia bluebells follows you through floodplain areas, and in fall, you can find pawpaws, or “custard apples,” a little-known native fruit that George Washington enjoyed for dessert.

If the full 10-mile trek is more than you’re looking for, there are numerous access points for shorter out-and-back journeys. They include Scott’s Run Nature Preserve, Langley Fork Park, Turkey Run Park, Fort Marcy, Gulf Branch Trail at Gulf Branch Nature Center, Donaldson Run Trail at Potomac Overlook Regional Park and Roosevelt Island.

Walking the narrow, verdant path brings bald eagle and osprey sightings and the sounds of lapping shores and roiling eddies to awaken senses dulled by everyday Washington-ness. It’s so close to D.C. and all of its grand global importance, and yet it seems so very far away.

–Sue Eisenfeld

10. Fine Dine for Cheap

Want a white-tablecloth dining experience without paying white tablecloth prices? Take the elevator to the 12th floor of the Ames Center building in Rosslyn, where Culinaire Restaurant (www.artinstitutes.edu/arlington/culinaire-restaurant) cooks up dishes like ceviche with green bananas ($8), smoked brisket with cornbread stuffing ($10) and ricotta cheesecake with cherry compote ($3).

The hitch is that you’ll be serving as a guinea pig of sorts, given that the 40-seat high-rise hideaway is run by students in the International Culinary School at the Art Institute of Washington. Over the course of a semester, students rotate through every station in the kitchen and dining room, taking turns as line chefs, servers and dishwashers.

Culinaire’s seasonal menu (it changes quarterly) is short and sweet but is careful to include meat, fish and vegetarian options. The place is a solid pick for a quiet business lunch or a night off from cooking, provided you’re willing to cut the kitchen and servers a little slack if your meal is less than perfect. (“Perfect” being relative, insofar as the chefs-in-training here can still sear a piece of salmon better than most home cooks.)

The main drawback: It’s a dry establishment. No alcoholic beverages are served, and there is no BYOB policy. Hours of service vary, depending on class schedules, and reservations are recommended, so be sure to call ahead. And bring your appetite.

–Jenny Sullivan